Reference documents are a superior alternative to dictionaries because they are genuine primary sources, and not based on guesses some lexicographer made a century ago. However, very few translators are able to use these documents for legal translations due to the highly abstract and social nature of the legal process, not to mention how specialized and technical the law is. Fortunately, there are effective techniques to solving this challenge, which I will describe below. In order to provide a scientific foundation to describe what fundamentally constitutes legal language, I’ll first introduce some basic neuroscience concepts about how the human brain organizes language information. Next, I’ll introduce the most useful linguistic theories for solving highly sociocultural language translation problems like those seen in legal contexts, namely Systemic Functional Linguistics and Discourse Analysis. Mastering these tools can mean the difference between success and failure for a translator working with legal documents.

Social Nature of Legal Documents

My experience is primarily with the Chinese-to-English translation of legal documents, which is so hard to do that typical translators will simply give up and offer the client gibberish. These translators lack a good conceptual foundation for their work; they ought to think of why legal documents exist. The reason that any legal document ever comes into being is that ordinary people in society need to achieve something; for example, if two people in China want to marry and establish mutual inheritance rights, they must get married. Otherwise, an estranged parent can seize the marital home in the event of a spouse’s unexpected death.

Marriage in most common law countries is achieved through a marriage license, while in the PRC, a marriage certificate is used, 70% of which is devoted to reciting rules from a regulation. A minor difference exists because of the PRC’s central planning tradition and arranged marriages, as opposed to the “spontaneous” order of common law countries. In the business context, where most work happens, a document such as an office lease exists because a company wants to obtain office space and eliminate the cost of having to suddenly move its furniture and people elsewhere every month. The lessee in an office lease also wants a good space that meets the needs of company employees, and to ensure some essentials like winter heating are consistently provided.

The needs of human beings and, more broadly, organizations of human beings are remarkably uniform across industrialized human societies. People need shelter, food, safety, belonging, esteem, and accomplishment. These people organize together in order to meet those needs, which then takes the shape of companies, which have further needs: investors joining together to enter a business need a way to control how their money is spent and get returns; employees need clear rules guiding their activities and guarantees of fairness and compensation; companies need a stable place to do business; and businesses producing bulk goods need assurance that buyers will actually pay for the completed product and buyers need assurance that the products ordered will be delivered.

These needs are remarkably uniform across industrialized societies because, to date, only one major economic model has succeeded in industrializing a country anywhere, and only one body of social practices in business has succeeded anywhere. Ancient societies are different: for example, Chinese has a word for “etiquette” and “face” that lack direct English equivalents; romanizations are needed to better explain why Manchurian-Mandarin translators received severe corporal punishment for their mistranslations—for making the Emperor lose “face” under the “etiquette” system. The old system of punishments revolved around the Confucian theory, where “face” became a measure of a person’s social standing within that construct. A modern Chinese corporation and its stocks differ very little from its American counterparts; China tried using Communes instead of corporations but didn’t like the results, so we now all use similar legal entity structures.

Social Reality Emerging from the Brain

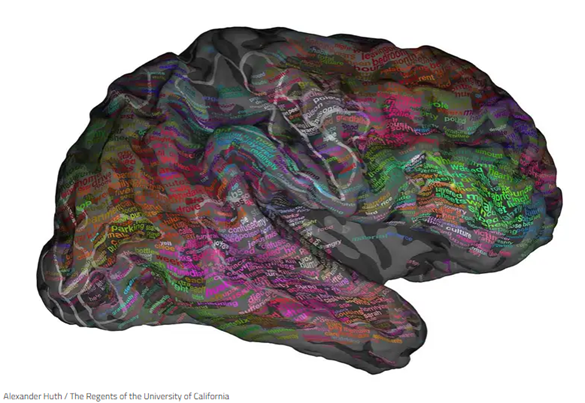

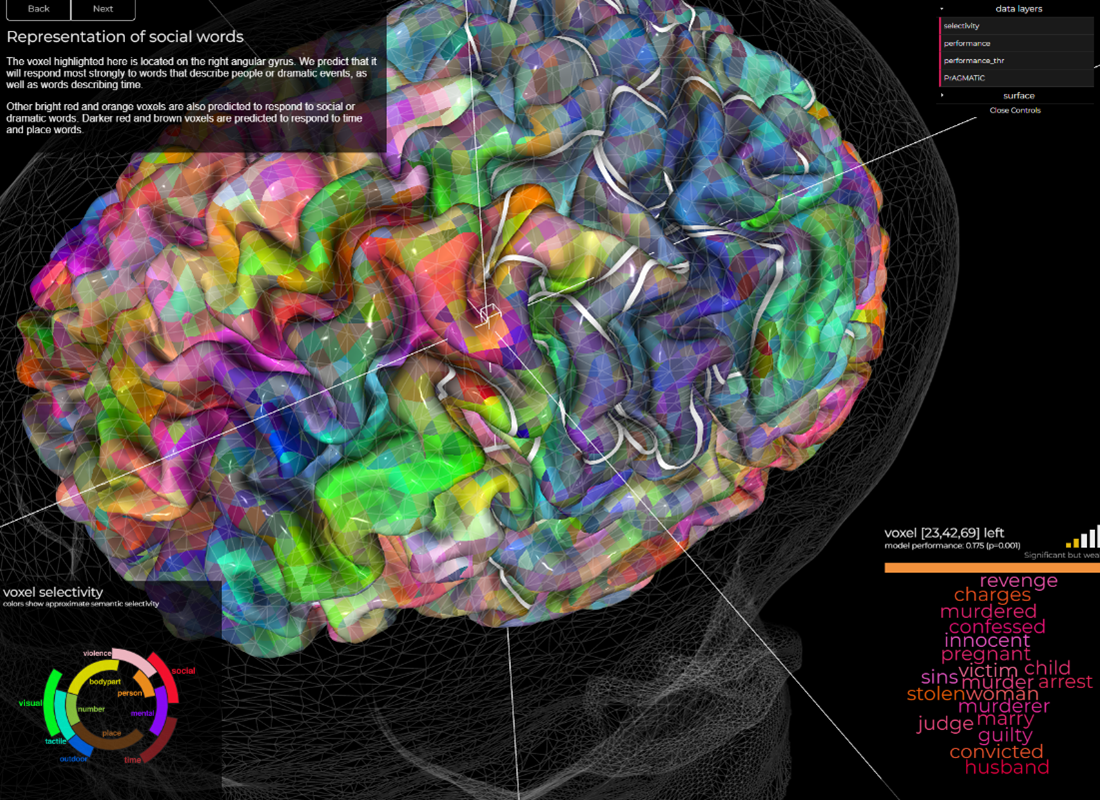

For the Chinese-to-English translator, these fundamental facts about the way the modern world works provide a physical foundation for how to structure legal translation work. The foundation is physical in that we know that human beings in both China and America are physically doing these tasks, and that language processing physically occurs in the left hemisphere of the human brain and around a brain area called the Sylvian fissure. Alexander Huth at the University of California even mapped individual words to an interactive online brain map.

Above we have a Word-to-Brain map. Word-to-word translation theories and beliefs don’t hold up under this model and, I am certain that if you were to take genuine bilinguals and do brain maps, equivalent words would not have equivalent placement in the brain. Even many English synonyms occur in different brain regions because they are more than just equivalents. The word-to-word theory is inconsistent with the neuroscientific model for several reasons. First, every individual’s brain semantic map is different: there is no fixed word meaning. A different experience with a word produces different brain maps.

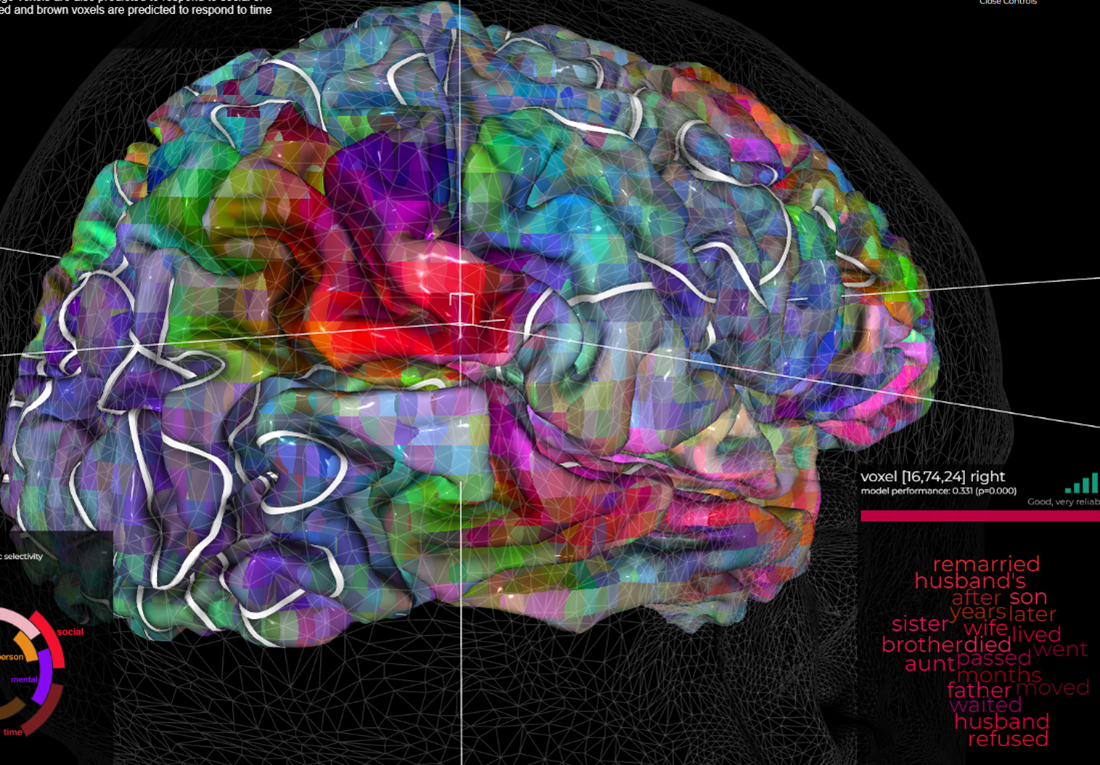

Second, types of words, color-coded in the image, cluster together, indicating a relationship between language production and physical experiences—for instance, green for visual and red for social are shown physically clustered in the same brain regions. To further illustrate this, think back to the marriage certificate example from earlier; five key words about inheritance rights from a spouse all occur within the same voxel [16, 74, 24] (they are: remarried, husband, wife, died, and passed). With the many thousands of voxel points in a typical brain map, the odds of all five words occurring in the space voxel randomly are lower than 1 in a Quadrillion; I’d guess a thousand times lower. That is to say, the words in a translation assignment can be found within a space in the brain where information related to that type of experience is stored. Physical social reality is experienced, stored in the brain, and associated with a word. The task of the translator, therefore, is to find a way to accurately match the language production of two different languages back up with the physical social reality stored and encoded in that voxel space.

Since brain science is too expensive and in too early of a stage to even begin doing comparative semantic mapping between Chinese and English speakers, a linguistic theory is needed to provide a solution that fits within the neuroscience findings. Fortunately, English linguist MAK Halliday discovered such a theory during his years at Peking University and developed it into perhaps the most ground-breaking linguistic theory of the 20th century: Systemic Functional Linguistics.

Systemic Functional Linguistics 101

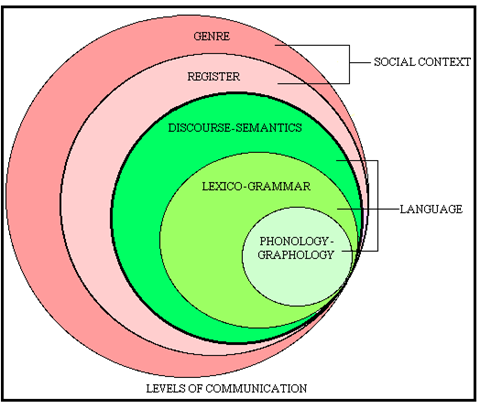

The systemic functional linguistics (SFL) topic is extremely expansive and is an entire professional specialization and too long to describe here. A good introduction can be found online by UEfAP, which should be read by translators not familiar with the field. For legal translation purposes, this diagram of the levels of communication described in SFL is particularly important for us:

UEfAP, Andy Gillett

In the marriage license translation example above, the majority of translators will simply look at the dictionary and translate word-for-word. This focuses solely on analyzing the translation answer in terms of the inner circle of the onion diagram, phonology-graphology. Rather, the several layers of the communication “onion” should be peeled back one by one.

The genre of a marriage certificate is the Marriage Law, which is codified in China but not everywhere else. The marriage law itself has several different registers: for example, there is a statutory register in the legislation and courts, an administrative register used by the bureaucrats who process marriage registrations, and there is also a colloquial register related to the marriage law seen in the marriage counseling service offered by the Chinese government. A single topic, such as the Cooling Off requirement for filing a divorce, is described differently by the statute and courts than by the government bureaucrats who process marriages. In fact, these two registers happen in different places by different people. The statutory register is used mainly by judges in the People’s Court which, in Shanghai, is several kilometers away from the 1-on-1 Classroom facility housed in the marriage registrar office in each of Shanghai’s districts.

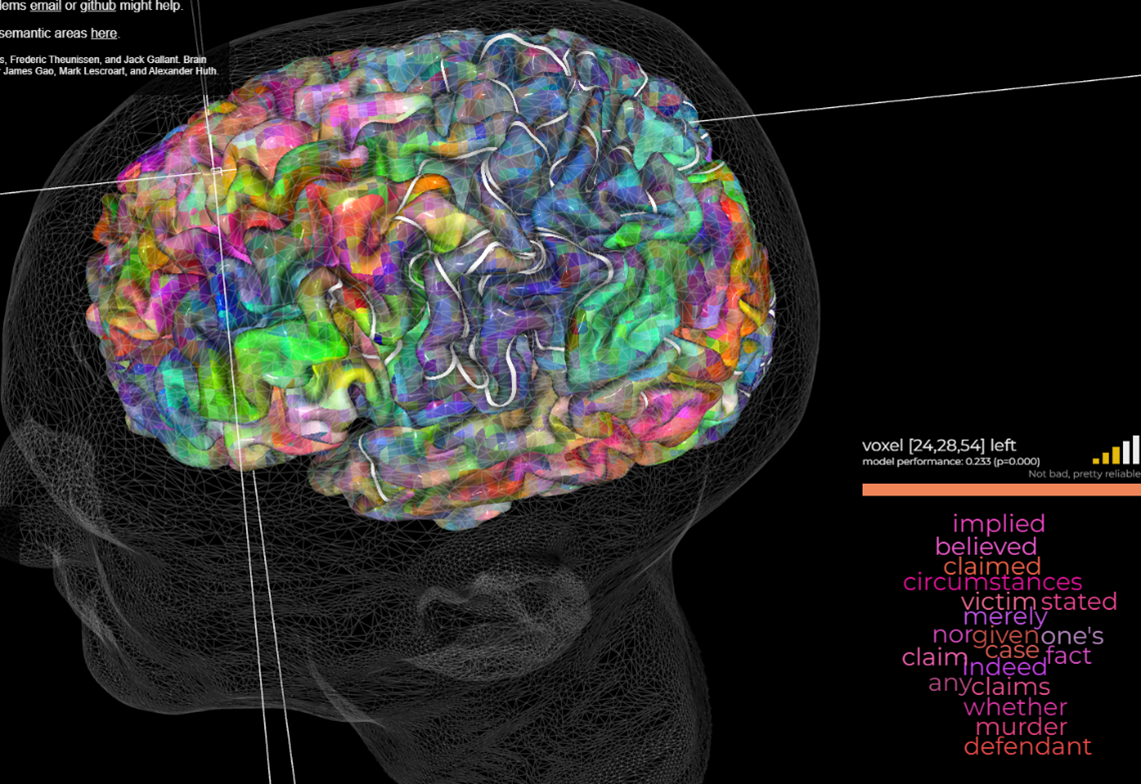

The fact that each register uses different people and places is crucial to understanding their language use. Refer back to the neuroscience semantic image above. How might the marriage counselor’s brain semantic map differ from the lawyers? I would expect the marriage counselor’s semantic map around the word “defendant” to look more like this than the second image:

For the lawyer, however, this poor-performing voxel where “husband” co-locates with common divorce court themes like judge, revenge, sins, innocent, victim, and woman, is likely to be much more dominant brain activity. In this case, it speaks to the divorce court and Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) stories about how husbands seek revenge on innocent female victims for sins that never happened.

Once the genre and register have been identified, we can finally begin looking for reference documents to analyze the next layers of the onion, that being the discourse semantics and lexicogrammar. The semantic map is, importantly, based on correlation and is not fully understood. However, I wanted to drive home the point that words and language are closely related to the physical brain, not abstract definitions.

Discourse Semantics Analysis

The pioneer of discourse analysis, which is now usually done as computer-assisted discourse analysis, was Norman Fairclough, who developed an entire field of linguistics study from this one layer of the onion. Like the foundational systemic functional linguistics, learning how to do a discourse analysis is a book-length subject. For legal translation purposes, unlike news media and government communications analysis, we can use a relatively straightforward approach to analyzing the nature of discourse within the specific genre and register identified. In the above example about a lease contract, I introduced how the lease agreement is used to meet human needs that occur in physical reality and that these needs are fairly uniform across human societies. That means what people say in a lease agreement and how they say it will also be fairly uniform within the community of practitioners. Therefore, discourse analysis fuses both sociological and linguistic (sociolinguistic) investigations into what the society is doing and matches that with how people in the society are talking.

If you look at ten office leases from the SEC EDGAR database, you will see that all ten leases are talking about basically the same sorts of things, using the same sorts of grammar, and the same sorts of vocabulary. There will be rent price, start date, and end date clauses and also prohibitions on things like subletting to other tenants, who are potentially unreliable. Chinese leases are much shorter than English leases because lawyers in China tend to charge by the lease and they can finish the lease faster if it is shorter. As a result, when translating leases originally in Chinese, a single typical US commercial lease will cover most pertinent subjects. Of chief importance in the discourse is that you will find that the same things are said repeatedly talking about the same events, including phrases such as “including without limitation” where such phrases are a single unit that always appears together with the same function. These repeating things in the discourse, the how things are said, comprise the inner layer of the SFL onion diagram, that being Lexicogrammar.

When arriving at the final lexicogrammar, note that we first identified the genre and the register, paying attention to the people and places involved, and used it like a map to identify the relevant model discourses. This is especially important for Chinese native speakers because Mandarin Chinese uses a unified word meaning system where words have a much more uniform meaning from context to context, whereas English word meaning can vary wildly in different contexts.

Lexicogrammar-to-Lexicogrammar Translation

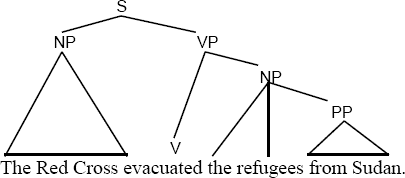

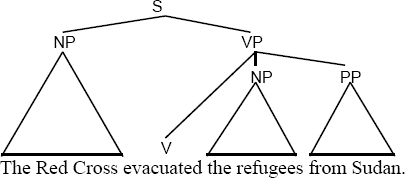

Lexicogrammar in SFL is a term that simply combines the words lexis and grammar. Halliday’s point is that words and grammar are interdependent and that if a word is separated from its lexicogrammatical unit, the word loses all meaning. Therefore, word-for-word translations are almost always considered wrong: they take each word away from its lexicogrammatical unit and therefore destroy the meaning intended. Lexicogrammar is also a big topic and reading a book or at least an article on it is worth your time. To grasp just the fundamental basics for this exercise, the website Polysyllabic has a useful article that describes sentence diagramming, in some places following insights from Halliday. The article points out that, in two different discourse semantic contexts, the same sentence “The Red Cross evacuated the refugees from Sudan” can be diagrammed and grouped into different units because it is ambiguous:

Notice in these diagrams that units in the sentence are not individual words but groups of words, and that how and where the grouping occurs tells us whether these are Sudanese Refugees not in Sudan or perhaps another nationality of refugees that happened to be in Sudan. In the original newspaper article, these were Sudanese Refugees being evacuated from New Orleans to escape Hurricane Katrina.

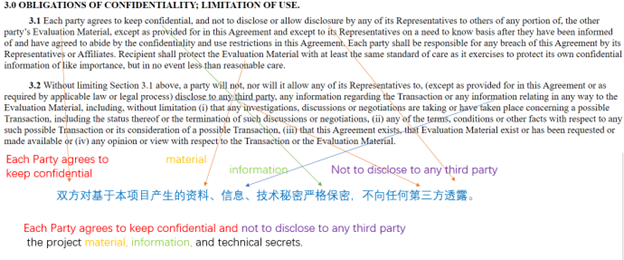

Identifying units of meaning, following Halliday’s lexicogrammar concept where parts of grammatical syntax comprise the word’s meaning when within an expected discourse context, makes it possible to translate sentences coherently. In order to make this a bit clearer, I have put together the following diagram which shows how two legal documents can be put side-by-side and lexicogrammatical patterns can be identified as units and matched almost totally between two matched documents. Below, I show a lease contract from SEC.GOV in the EDGAR database, matched to a translation task, which is the text shown in blue, bearing in mind that this is a highly simplified example and that between each set of language is a human mind that has rich experience.

In this diagram, I have color-coded a number of items and extracted them into text boxes, for example, “Each Party agrees to keep confidential” here is a composite of three units, but one that also forms its own repeating unit: (1) Each Party (2) Agrees to (3) Keep Confidential. Readers of Chinese will notice that, if translated word-for-word, the sentence would come out as “Each party for materials, information, and technical secrets founded on the project will not disclose to third party.” These sentences mean exactly the same thing, or at least are intended to mean the exact same thing, but the word-for-word sentence is likely to make little or no sense to someone unfamiliar with Chinglish or other word-for-word translations. Why do we prefer to use the easy-to-understand sentence as opposed to the word-for-word sentence?

The main reason for doing something like this is, if you go back to the semantic brain map, someone familiar with Chinglish may indeed have a brain map that makes the correct associations with physical reality. However, a typical reader will only be able to process fully formed and correct lexicogrammatical units that are also organized according to the onion model of systemic functional linguistics shown above. Thus, while the two sentences can be equally correct for a translator, they are not equally correct for a typical reader, because the standard of correctness is not whether translators agree, but rather whether the completed translation will be useful to a human reader.