Inaccurate translations are now being weaponized in the legal process to attack what are actually innocent parties. Much of the behavior is closely linked to the rise of “Lawfare,” the practice of strategically using the law as a weapon of war. Evidence of this phenomenon had been largely speculative until relatively recently, when newspapers and academics began investigating and uncovering cases of manipulated translations being used to harm people. How can parties protect themselves? The litigation system allows putting different translations in front of a jury, which can weigh the credibility of the different versions and decide which is accurate. Since litigators primarily weaponize inaccurate translations against unsuspecting parties, and many incompetent translators readily admit their lack of knowledge when asked, defeating weaponized inaccurate translation is not difficult.

Lawfare

The notion of weaponizing legal translations found immediate adoption in law and has expanded significantly with the idea of Lawfare. Lawfare, apparently a Chinese invention proposed in a People’s Liberation Army book, gained academic notice in the book Lawfare: Law as a Weapon of War, which described the practice in the Middle East (human shields) and the numerous ways in which Chinese national security actors used it to further China’s national security interests. Upon his entry to the White House, China national security guru Michael Pillsbury would then launch a program that caused the whole Lawfare concept to truly explode onto the scene—the China Initiative.

Like the purported Chinese Lawfare it sought to retaliate against, the China Initiative resulted in a large number of prosecutions against Chinese corporations and scientists on national security grounds. Most likely, these scientists or corporations had, at least privately, expressed some animosity towards the United States or did something, like providing telecommunications equipment to Iran, that turned up in an NSA intercept. As a result, they had the hammer of American law brought down against them. Much of the cases involving scientists seemed to have been related to Thought Crime: going to the United States while having thought anti-American things. Those thoughts are perfectly legal, so Lawfare is used to rigorously attack political enemies.

This last line comes from Holding the Line, a recent book by a former United States attorney for New York in which the author recounts how the Trump White House directly ordered him to manipulate the law to persecute Trump’s political enemies. While the book doesn’t get into Huawei, it’s safe for us to assume that Huawei’s legal case was indeed a political Lawfare hit job since it occurred in New York.

The weaponization of legal translations has also recently been documented in asylum cases, as reported by well-respected newspapers, which we’ll need to investigate to understand how legal translation is weaponized against technology professionals and companies.

Asylum Case Findings

A unique laboratory for the misuse of legal translations is the asylum context. The low burden of proof for the state to make an adverse judgment in an asylum case, the lack of direct penalties, and the low social status and power of claimants all make for an environment where people are likely to be abused. The Routledge Handbook of Discourse Analysis even dedicates an entire chapter to how judges misinterpret even reasonably accurate foreign language interpretations in ways that are highly prejudicial to claimants. This raises the question: what would happen if the immigration system were to begin knowingly introducing incorrect translations? A major newspaper, The Guardian, recently reported on how the US immigration system is introducing machine translations that greatly distort claimants’ testimony when making asylum case decisions:

“The woman was using the term colloquially to describe her father, but the translation service translated it literally to “my boss.” Her asylum application was denied. Not only do the asylum applications have to be translated, but the government will frequently weaponize small language technicalities to justify deporting someone,” said Koren, who used to work at Google Translate. “The application needs to be absolutely perfect.”

Here, we can see that federal government agents, with no personal stake in the translation, are quite willing to “weaponize” mistranslations produced by neural machine translation systems against people who lack access to accurate translations. Often, the translated evidence is knowingly misrepresented against the claimants to serve a political purpose.

We can therefore reasonably infer that parties with a personal stake in the matter, such as attorneys representing dishonest businesses, would be willing to be significantly less honest than faceless federal bureaucrats. A particularly dangerous feature of legal translation in the language I work with, Chinese<>English, is how most official dictionaries and even legal English textbooks are filled with misleading and incorrect standardized translations. Few people, apart from highly bilingual professionals, are even aware of these inaccuracies. These professionals can thus selectively weaponize these kinds of routinized errors in litigation with impunity.

Huawei’s Case

While a public prosecution, the USA v. Huawei case set for 2026 is nonetheless a stunning example of how bilingual attorneys can weaponize translation against a party. In this case, the federal government, using its fairly expansive resources, seems to have realized that the dictionary-recommended phrase “ordinary business cooperation” in a translation for one of Meng Wanzhou’s PowerPoint presentations could be easily weaponized to prosecute the company for banking fraud. The Department of Justice appears to have falsified translations of documents that repeated the same Chinese phrase found on Meng’s computers, by also retranslating them using the same dictionary-recommended English phase.

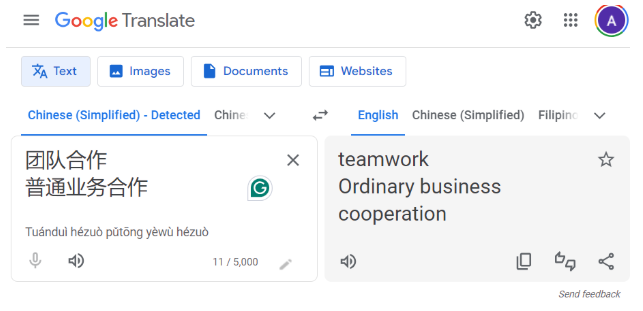

What’s the problem with that? No reasonably competent translator could have organically arrived at that phrase as a match to the original Chinese—it’s never been used before in business English and suddenly arrived on the scene as an invention by translators in the Meng case. It’s not naturally occurring in English, meaning that even if the prosecutors don’t know Chinese, they should know that it’s likely misleading. The source Chinese word hezuo, which prosecutors and the FBI falsely claim must refer to third parties, can refer to first, second, or third parties. For example, the phrase tuandui hezuo is usually translated as “teamwork.” You don’t need to know Chinese to see this, you can just plug it into Google Translate:

You can even experiment yourself, entering 团队合作 and 普通业务合作on the second line. Most likely, the translation was initially derived from Google Translate and the translator falsely assured Meng Wanzhou that it was accurate and that HSBC would clearly understand the message. What happened next is astounding.

During the settlement phase with Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou, the FBI acquired documents from her computer and falsely translated them to track onto the scam translation, using the context of Meng’s documents to get an admission that “ordinary business cooperation” implied a third-party reference. In the real-world facts of the case, Meng had simply provided insufficient information to HSBC. HSBC obviously had the capability to understand the Chinese documents but was eager to look the other way and deflect blame onto the client, manipulating the translation to create a parallel universe of “alternate facts” against Huawei. Then, Meng signed off on the DPA that the facts were true.

How could Huawei have protected itself? If I were a Huawei lawyer in this scenario, I would be getting highly credible, highly qualified translators to submit their own translations of the case materials, particularly translators who will not blindly follow Google Translate’s recommendations—thus breaking the link between those documents. Further, I would have a translation expert analyze the original translation and identify its obvious fraudulent nature to a translation department, as well as the numerous ATA ethics rules broken by that translator (and the FBI). Moreover, I would have this done under a translator’s seal.

In any litigation, translators are expert witnesses, and juries assess their credibility. When a party brings forward evidence from unqualified translators or even unsupervised AI, the lack of credentials alone should be concerning. Moreover, translators can take action to improve their credibility in the forum. Much like AI, most unqualified translators being weaponized to attack another party will often just freely admit they don’t really understand how these documents should be translated if asked directly; they are just filling things in that they found on the internet somewhere and kind of taking a guess. Why? Because that’s basically how the majority of legal translation is done: the content is hard, and translators are, for the most part, relying on guesswork.

Litigation parties can protect themselves by introducing translations with superior credibility into the litigation process, thus aligning the evidence to the truth and casting doubt on low-quality, disparaging translations.