The tiny English vocabularies of Chinese translators have resulted in a variety of absurdities that amount to much of what international society labels Chinglish. The new language, Chinglish, was able to emerge largely because of pseudoscientific beliefs among translator communities in China (and also Japan) that the involvement of foreigners in a translation into English would corrupt and lose the true meaning of the document. This belief restricts the possible range of vocabulary that can be utilized to about 10% of an educated native speaker’s level, or 5,000 words overall. This results in the excessive use of certain words like “department” or “relevant” in Chinese to English translations, and hides the true meaning of the texts. Below, I will describe the origins of the tiny vocabulary problem and actionable solutions that can be used to improve translation service quality.

Social Pseudoscience

One defining characteristic of Chinese legal translations is the rejection of the native speaker rule for translations. Not only is it rejected, but the industry more or less blasts it with explosives. In Europe, the native speaker rule is taken to another extreme where people who aren’t native speakers are expected to be excluded from the translation. In China, and in some other countries, notably Arabic and Japanese-speaking regions, there is an idea that nobody who isn’t a native speaker of Chinese, Arabic, or Japanese, should ever be allowed to translate for those languages. As a result, there is a well-known rule at the United Nations where qualified Chinese and Arabic conference interpreters are rejected simply because their native language is English. For Arabic and Chinese, this can be described as the “no foreigners” rule because this is how the rejected linguists (foreigners) are characterized. In Japan’s case, numerous Japanese companies’ products in the late 1980s were commercial failures abroad due to attempts to apply this sort of rule, leading to big Japanese corporations and the government abandoning the rule, despite some small businesses apparently still sticking to it. Thus, in contrast to the big Japanese titans, small and medium businesses in Japan continue to be commercial failures in the international market. Some Chinese companies—notably ByteDance—are trying to learn from the Japanese experience in their international localization efforts.

A big cause of the failure of all three cultural groups to succeed internationally is the “no foreigner” rule’s ability to contribute to the tiny vocabulary problem. The tiny vocabulary problem is basically the compression of a 60,000 source word vocabulary into a 5,000-word target language output; although grammatically correct, the tiny vocabulary still makes the work product useless for anything other than pleasing other tiny vocabulary translators. The scientific basis for the tiny vocabulary issue can be found in the numerous scientific studies showing what English vocabulary achievements language majors attain by the time they graduate from college. In Europe and the US, at a typical language major’s graduating proficiency level, you are looking at a vocabulary size of about 5,000 words.

Native speaker college graduates of other fields know over 20,000 words, but writers in sophisticated contexts such as literature and legal can reach a vocabulary of about 60,000 words, and Shakespeare himself used 65,000 different words in his works. Translators moving from Chinese to English, who can fully understand the source texts of their authors, often attempt to cover a vocabulary of about 65,000 words used in texts produced by many authors working together in their native language with an arsenal of just 5,000 English words, or 13 Chinese words to each English word.

Organizational Effects

The tiny vocabulary effect has an outsized impact when a translator is translating into their second language, especially where non-native translators are dominant in the language pair or field. In the Chinese legal translation services industry, translators are typically expected to work at very high speeds when translating into English, often two or three times as fast as Spanish-into-English translators do, and correspondingly their per-word rates are much lower. This forces translators to rely primarily on intuition and memory in order to match up the words. The practical effect is that if the real target translation would encompass a 60,000-word vocabulary, the translators will be forced to condense it into a 5,000-word vocabulary. This basically means that if there are 12 words that have similar but distinct meanings, the translators would convert all twelve words to the same exact English equivalent.

An example brought to my attention by a legislative translator in Beijing is an absurdity that resulted when translating multiple Chinese words into the English “department.” Readers encountering Chinese-to-English translations of Chinese laws may be familiar with the strange expression “relevant departments,” which has no equivalent in American law despite having the same origin, meaning, and intent as another expression in American law, specifically “appropriate agency.” In this context, a “relevant department” is an administrative agency, but since translators working with administrative law had never heard of administrative agencies, they merged this into the word department. The legislative translator went on to point out that every level in the hierarchy had been translated as “department.” While this was not noticed at first, eventually someone made an organization chart where each of the six levels was labeled “department.”

If you look at the organizational charts of American administrative agencies, you will see that there is an administrative agency, and below that a variety of terms are used: division, directorate, section, group, unit, office, bureau, and department. There is a fairly rich vocabulary being used here, much like in Chinese, and what is definitely absent is the repetition of department, department, department over and over. What’s really fantastic about this situation is that it persisted for 40 years before anyone noticed the issue and decided it needed to be resolved. A retired legislative translator noted that foreign opinion on Chinese-to-English translations had been excluded for decades because of a belief that foreigners could not understand China. This led to the decision to translate half a dozen different Chinese words as “department.” Sometime around 2010, when the New York Times began ridiculing Chinglish, younger generations became more sensitive to the fact that rendering Chinese sources into a word salad of English does not reflect a true mastery of the essentials of Chinese culture, rather, in linguistics, would be considered symptoms of a serious disease like aphasia. “Department, department, department, department” was accepted as a fundamental truth about China for decades because everyone was trained to utilize the same tiny vocabulary.

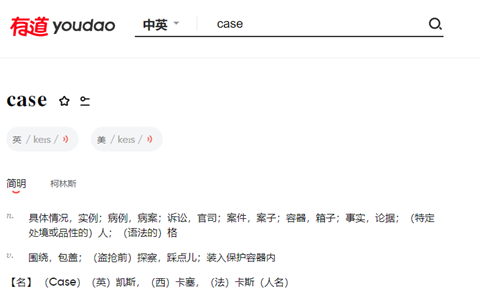

The Youdao dictionary nonetheless still lists five of the six different words that were, at least once, all translated as “department.”

Another more recent case that has eluded detection is ironically the translation of several unrelated words all into “case.” For example, several legal words in Chinglish are all referred to as “case”: project, matter, precedent, and case. Chinese dictionaries also show this phenomenon, so that a translator at a law firm could mash these various words together to form a sentence like “The translation case about the data protection case for the Facebook case needs to be done before the FBI opens a case.” Using real-world English, in that situation I might say something like “The project to translate data protection precedents for the Facebook matter needs to be done before the FBI opens a case.” In Chinglish, translators talk about a “case” where there is a discrete request from a client that can be divided into “projects” and they feel the need to say “case” to distinguish from the English word “project,” but due to their tiny vocabulary wind up merging four law firm practice management terms into one. (The Facebook example is a pure hypothetical intended to represent the plight of Chinese technology companies). Like with the department example, a dictionary shows a dozen Chinese terms matching to the one English term:

In practice, where this tends to cause problems is when a legal department working on compliance matters has two separate Chinese terms, anli bianhao and anzi haoma, to describe two distinct situations, but the translators will take two totally different sets of words intended by people in China to mean different things and render them into the same term: case number. As a result, translators can actually frustrate, rather than promote, the corporate compliance process, because they are now effectively covering up important intended meanings without even thinking about it.

Solutions to Tiny Vocabulary

There are three easy solutions to the tiny vocabulary problem, which are things I’ve written about before. First, the most difficult yet rapid solution is the use of computer-assisted discourse studies methodology. Discourse studies can enable any person to rapidly catalog and utilize the vocabulary of a relevant field. Additionally, no preparation is required to apply discourse studies techniques to a particular translation project. A drawback is that, while they can be deployed rapidly, discourse studies techniques are very inefficient when used on a single translation project since you could acquire the necessary vocabulary much faster using organic techniques. This leads to the second technique, off-the-job training in the second language, a technique developed by Betty Lou Weaver, a university professor specializing in high-level language acquisition. Statistically, fewer than 15% of translators will succeed with this technique, simply because that’s about the percentage of college students studies found are interested in acquiring “deep” knowledge – a statistic I can observe among translator populations today. A lack of motivation toward deep learning predicts a lack of motivation to follow Weaver’s strategy for success as a translator. If you fall into the 85% of translators who lack deep learning motivation, I recommend you consider working on the business side of translation, where personal experience is relatively more important.

Finally, the third strategy is the hardest to apply but is one that has been used successfully by major Japanese companies like Sony and Nintendo, and that is to transition from the traditional insularity mindset exemplified by the “no foreigner” rule used for Arabic, Chinese, and Japanese. The basic reason is that if you work with someone who has a different ethnic background and respect them as a professional, you can expand that 5,000-word vocabulary up to a 60,000-word vocabulary. This is something that contravenes tradition and prejudices, especially those held by very old people, and will be resisted simply because it requires a significant change in mindset. Many people from insular cultures believe that outsiders cannot understand their culture, but that they can easily understand outsider cultures. This is really a form of confirmation bias: when these people read news reports about their own country, they feel wrongfully stereotyped. When their own media wrongfully stereotypes foreigners, they uncritically accept it as truth. This leads to a mindset among translators that only people from the insular group can translate because the ingroup is always seen as being right (i.e. confirming one’s own opinions), whereas the outgroup is seen as being wrong half the time (when reporting on the ingroup). A huge maze of logical fallacies and cognitive biases creates a fortress that secures the position of the tiny vocabulary bias in the minds of these translators. At the same time, it’s in the interest of these same translators to think logically, because they are actually causing their stakeholders to repeatedly fail, which causes stakeholders to devalue translators and therefore pay them less. As a result, failing to apply the third strategy results in a paradox where translators believe strongly in two things: first in their self-rightness, and second in that they are underpaid.