The bizarre Chinglish phrase “relevant departments” is an opaque term understood by virtually nobody. But rather than being a so-called “invention of the Chinese people,” as translation theorists often insist, it is really a product of Platonic metaphysics applied to translation.

While not native to China, translation between Chinese and English historically occurred primarily through the engagement of European missionaries visiting China. This has led to the development of the impenetrable, incomprehensible translations often decried as “Chinglish,” particularly in governmental and legal texts.

More contemporary linguistics science indicates that language functions very differently from the old Platonic ideals. This article examines how a latent Platonic tradition in translation practice is creating cultural and communication barriers and will introduce modern science-based alternatives to improve clarity and accuracy.

Relevant Departments Is China-Unique and Highly Confusing

Several years ago, when I supervised a group of students translating several local Chinese laws into English, they participated in a conference at a local law school to share their findings. The conference organizer was a computational linguist with expertise in big data corpora analytics and was particularly interested in my ideas about following scientific principles when analyzing language. Even the students and several professors were on board with the idea of using translation to recognize that China has government agencies just like any other country.

One student reasoned that there shouldn’t be this artificial chasm between East and West created by translators, where English speaks of “agencies,” but in China, they are “relevant departments.” Likewise, in Chinese, the government is comprised of bumen while every other country uses jigou for equivalent entities. This kind of vocabulary parallelism, she argued, defeats the purpose of translation. The old guard of translation professors was quite shocked that this time-honored translation tradition was being challenged.

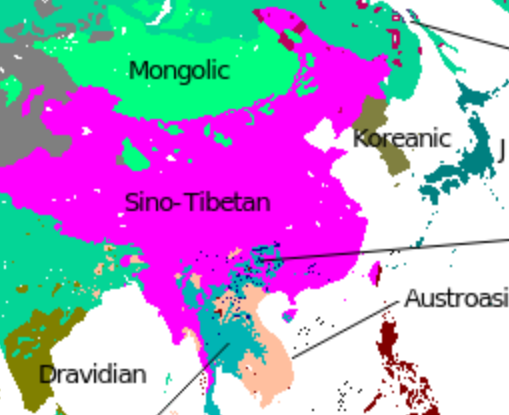

In the following sections, I’ll go over both the modern scientific principles and the ancient ideas of Plato. However, the point is to identify Platonic translation approaches and describe why they create problems, rather than attempting to prove historically that the translation method originated in Platonic thought. That said, we do know that Plato was enormously influential in the Japanese and Chinese translation communities from their establishment during Western contact, as translation at the time was dominated by missionary collaborations with Chinese and Japanese intellectuals.

Plato’s Ancient Beliefs Behind Modern Translation

The ancient view that Plato suggested posits a kind of heaven in which all concepts exist in their perfect forms, while our words and deeds are a mere reflection of these higher, idealized versions.

To provide a quick refresher on the parable of Plato’s cave, the philosopher uses the metaphor of shadows dancing on a wall to say that there is a higher reality of perfect Forms, of which things on earth are merely imperfect manifestations. This has been described as creating a kind of Platonic heaven as such:

Plato’s Theory of Forms is quite expansive, and if unfamiliar with it, you can find a short video overview of Plato’s Metaphysics on YouTube. The “Platonic Heaven” theory is so deeply ingrained in world translation practices that the recent re-translator of the Odyssey pointed out that all of the words in the translation are entirely different from those in the original.

I hypothesize that thanks to Jesuit teachings and tradition, Plato’s Theory of Forms is even more ingrained in East Asian translation practices. For example, the Employment Law textbook used in China’s law schools tells us about the terminology used for employers: “In China, this is known as a yongren danwei, abroad it is known as a guzhu.” The writer sounds like he’s saying that the United States and France use the Chinese word guzhu to express the idea of an employer.

Chinese medicine textbooks have a similar system of parallel vocabulary for Eastern and Western names for the same thing—the Western name, of course, being a Chinese word used only in translation. All of these authors subscribe to the Platonic Forms notion when they talk about Chinese words that are only used outside China, as they are ascribing to a kind of belief that there is an eternal Form for Chinese thoughts and an eternal Form for equivalent Foreign thoughts. Plato is, however, quite outdated, so I think it’s only fair to explore a 20th-century theory that achieves the same results but benefits from 2,500 years of additional experience: Heidegger.

While very complex, Heidegger’s work builds on the earlier Platonic school (particularly Augustine). As a very brief summary, Heidegger concludes that the essence of Being is fundamentally tied to human existence, which is always situated in a specific context and time, allowing for the understanding and interpretation of the world. He asserts that Being is revealed through our everyday experiences and interactions, emphasizing the importance of our temporal and contextual existence.

In his account of language, Heidegger asserts that language is the “house of being.” By this, he means that language is the medium through which the nature of Being is disclosed. It is in language that beings come into presence and are understood. Heidegger argues that translation should aim to preserve the essence of the original text. Here, translation’s role is to transfer expressions about “essence” (being) from one language to another. For the modern translator, no belief in a Platonic Heaven is necessary anymore—Heidegger’s theory achieves a different result by rooting language in fundamental essences.

Modern Linguistics Science Finds the Opposite of Essentialism

While very strong, Heidegger’s theory is increasingly undermined by recent advancements in linguistics. In his recent work Language vs. Reality: Why Language Is Good for Lawyers and Bad for Scientists, N.J. Enfield advances expansive evidence to demonstrate that the exact opposite of Heideggar’s view of language is true. Enfield argues that language excels in its persuasive and social organizing functions, helping to shape narratives and influence perceptions—an advantage for roles like those of lawyers.

However, language often struggles to accurately represent reality, introducing distortions and limitations that pose challenges for scientific endeavors reliant on precise and objective descriptions. The primary function of language, shaped by millennia of human evolution as a social species rather than a scientific one, has never been to represent being or essence in itself. Not only is this not a purpose, but getting language to function effectively to convey nuanced, complex meaning requires great effort and skill.

In the field of neuroscience, a salient earlier discovery related to Enfield’s findings on linguistic fictionalism is the ability to use language communication to implant false memories in other people. By presenting false narratives and using manipulated images, people can be led to tell stories about events in their lives that never occurred. In parallel with Enfield’s findings, we can see that, while language has powerful persuasive capabilities, it is so poorly rooted in objective reality that it also powerfully drives falsehoods.

A second salient finding is Hartry Field’s mathematical fictionalist proof of Newton’s equations, which shows that all mathematical symbols are fictional in that they do not correspond to any objective mathematical entities. When I asked Field in 2003 about whether theoretical quantum physics could be established with equal efficacy as mathematics, he said that, in his view, there would be no difference—only that doing so would be very tedious and difficult.

Here, I propose adopting Field’s assertion that linguistic and even mathematical symbols are merely fictional. Yet, as Enfield suggests, they remain essential to what Aristotle calls “human flourishing”—working together to do everything from organizing farming villages to discussing complex physics models for quantum computing. Finally, to make it extra difficult for ourselves, I believe that we should incorporate W. V. O. Quine’s Indeterminacy of Translation thesis—that is, his notion that, due to the infinite ontological variations in the signified concept affixed to a static sign, no translation or reference, as envisioned by Heidegger or Plato, can be possible.

Translators Are Not Infallible

This is a huge departure from translation tradition—the King James Bible translators not only believed they could reflect the certitude of a Platonic Heaven, but they also asserted that God guided them to make a perfect translation. Shortly thereafter, thousands of innocent women were executed as witches because of what later turned out to be a translation error. When we, as translators, assert our infallibility and develop theories to ground that infallibility, people come into conflict and get hurt.

This isn’t as crazy as it sounds. Consider that Newton’s Laws, while groundbreaking, are imprecise when measured against quantum physics. Engineers designing the field-effect transistors in your cell phone rely on huge “fudge factors” in their calculations to ensure that the lithium battery does not explode into a fireball when you’re on the phone. Indeed, there was a time when Samsung and Apple phones occasionally did explode—if we can accept the imprecision of physics calculations when using a cell phone that may explode against our head—why can’t we accept indefiniteness and uncertainty in a translation?

What Translation Looks Like in an Atmosphere of Impossibility

If we accept, based on our ontological commitments to neuroscience and anthropological linguistics, that as translators we cannot transmit “being” or directly reference a Platonic form, then what are we doing? In my view, we are reducing uncertainty and closing the intersubjective ontological gap.

As Quine indicated in Ontological Relativity, each person’s subjective ontology—their understanding and interpretation of the world—apparently differs significantly from others. However, as humans, we’re capable of coordinating and aligning our subjective ontologies using language. This coordination is needed for all sorts of everyday activities, but in translation, it can have enormous impacts. For example, in the upcoming USA v. Huawei case, the United States accuses Huawei of submitting false KYC documents that misled HSBC into approving a transaction based on a mistranslation saying Skycom was a third party.

As I have translated these types of documents long before Huawei’s case, I know that the Chinese documents would always use language that avoids making a clear statement about whether Skycom is a third party, because the Chinese hezuo is ambiguous whereas English, a low-context language, is highly specific. In this case, the role of language was to align Huawei’s ontology with HSBC’s so that HSBC could decide whether to approve the transaction or require Huawei to change its business model to something more legally compliant. The translation that caused the problem very much followed the dominant Platonist tradition, choosing a singular word to match the Chinese form of “hezuo.” And this led to immense controversy and violence.

Let’s go back to the examples of “relevant department” and “employers,” where translators are making assumptions that language either reflects a “Platonic Heaven” or, if they are well-read translators, a “House of Being” that represents essence. In this case, what kind of ontological alignment occurs through semiosis, and what kind of socially coordinated action does it facilitate? In our example, imagine that Amazon launches a fashion retail importing platform to compete with Shein and Temu, using the same kind of direct-from-China manufacturing supply chain and shipment methods to sell inexpensive, generic Amazon-branded products. To operate legally, Amazon will need to ensure labor compliance by its local China suppliers, and this means understanding three “who” questions:

- Who works?

- Who hires?

- Who regulates?

The theory advanced by China’s labor law textbook authors is that China doesn’t have “employers,” rather it has “units” that “employ.” This theoretical distinction can cause a lot of confusion. Particularly when numerous Chinese-language labor documents use the word “unit” over and over instead of the more precise terms for what it really is, an “employer” or “organization” depending on the context. This does not help with aligning subjective ontology to answer the three questions, because when an American Amazon compliance officer reads “unit,” they aren’t thinking about “who employs.” Nor does this help with navigating complex labor law issues and local labor expectations.

However, if we focus on aligning the ontology—harmonizing beliefs about the world between either communicative side—we would instead consider saying something like, “If the factory wants to use flexible hours scheduling to achieve just-in-time manufacturing efficiency, the employer must file for approval with the appropriate agency in its jurisdiction.”

Using terms like “relevant department” or “unit” hides who is doing what. Only someone with a master’s degree in China studies might have an inkling of the intended meaning. However, for a global compliance officer, that level of specialized knowledge is not necessarily realistic.

The implications for coordinating behavior are significant. Lots of fashion retailers in recent years have been accused of extremely severe labor violations, even forced labor allegations, based on the same translation ambiguities as above. If Amazon were found to be using suppliers that violated Chinese labor regulation’s very specific forced labor provisions (such as the prohibition on confiscating workers’ ID cards), then it could result not only in regulatory penalties, it could tarnish the company’s reputation globally and lead to justifiable conclusions that certain nefarious acts were ordered by executives…even if it was merely a translation error.