Today, the majority of legal translation from Chinese occurs through the English as Lingua Franca process. While attorneys providing legal advice in this context feel that they are merely “using English,” the manner in which English is taught in East Asia, using the so-called “translation approach,” ensures that the output is fundamentally a translation and not natural language. Moreover, the quality of such a translation would be relatively low and lacks a readily available Chinese source document.

Tests on professionals’ language done in China show a clear transcoding structure, where algorithmic back-transcoding can effectively restore the intended source Chinese document. The result is amateurish translations into English that are misleading to users. Such an approach may have been the best available several decades ago but, following globalization and modern technological advancements, it is now outdated.

Machine Translation “Transcoding”

English as Lingua Franca type ESL in the context of Chinese, and likely other languages, has a remarkable feature in that it closely overlaps with machine-translated language and logic. In a series experiments with real business writers, I converted their writings back to Chinese using machine translation and showed the results to the authors to get feedback on their perception of the accuracy of the machine’s understanding of the original. Quite remarkably, all the writers found the machine-translated Chinese version totally accurate, even when the English version made little sense. While this might seem paradoxical, there is a good scientific explanation for why incomprehensible English could be machine-translated back into proper Chinese, otherwise known as “transcoding.”

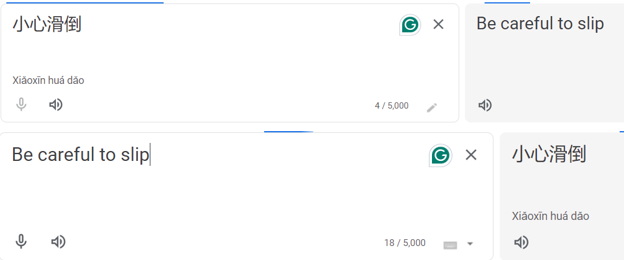

In translation studies, “transcoding” is a more technical term for literal or word-for-word translations, where each word is treated as a symbol in a code, and 1-to-1 exchanges between symbols in two different sets of codes are made. The results of this process include those infamous Chinglish signs or “Songs by Google Translate.” Here is an example to illustrate the phenomenon: the famous Chinglish sign “fall down carefully” continues to be mangled by Google Translate to this day, rendering it as “be careful to slip.” This happens because Google Translate, and other freely available machine translation tools, essentially plagiarizes the work of countless incompetent translators who use English in this manner. If we take the broken English “be careful to slip” and put it into Google Translate, what do we get? The Chinese expression “xiaoxin huadao,” which means “slippery when wet.” Nevertheless, sign makers have recently gone with an even more ultra-literal and less accurate translation: “Caution! Slippery!”

The relevance of the machine translation is that it very clearly reveals the nature of the English as Lingua Franca as transcoding. The English seen in the various Chinglish signs, whether done by real people or machine translators, is nonsense, but the nonsense transcodes back into a perfectly accurate Chinese expression. What this means for those using English as a Lingua Franca who produce English that can be transcoded back to perfect Chinese (or another language), is that they have essentially learned an interlanguage. This interlanguage essentially functions as a transcode from their native language to a “translationese” version of English.

Early scholars of the Chinglish phenomenon noted that incompetent Chinese-to-English translations had been incorporated into English textbooks used in China, with the result being that hundreds of millions of people were taught a translationese-based language. Moreover, I believe that the advent of effective back-transcoding technology also changes the status of English as a Lingua Franca.

Suppose that a law firm or company has technical writing in poor English and needs a linguist to revise it into proper English. What would the most rational course of action be? Use DeepL or another tool to translate the document back into Chinese, determine what it really means, and proceed to translate it into English. A more classical approach would be to edit the English using a copywriting approach, and indeed, many translators do advertise copywriting services since they are so frequently sought out in English as Lingua Franca contexts. Even with copywriting, there is nonetheless a huge language and cultural barrier between the translator and the intended meaning, a barrier that does not exist when working with the native-language version. Thus, with the advent of transformer-based artificial intelligence back-transcoding capabilities, these interlanguage texts can be easily restored back to their native language and accurately translated according to the intended meaning.

This whole process raises some questions about the continued rationality of the English as Lingua Franca + Copywriting approach, and whether it may now be outdated. There is good rationale for organizations to consider using an approach like this. For the most part, translation services for legal texts or technical writing are absolutely incompetent. All the translators do is simply look up words in a dictionary and organize them according to grammatical rules, resulting in incoherent translations. Meanwhile, lawyers or Engineers with some skill in English are having conversations, meetings, and writing memos about the subject matter and getting enough feedback to achieve minimum intelligibility. Ironically, they tend to perform much better than language specialists. This discrepancy has not gone unnoticed in the translation industry; numerous commentators have noted that subject matter expert staff in major corporations typically possess superior English skills compared to translation staff. Combined with the fact these experts have real technical skills and are capable of performing linguistic tasks better than the language specialists themselves, subject matter experts typically command salaries two to three times higher than those of language services staff.

While the English as Lingua Franca phenomenon became the new normal during globalization, it is not normal or efficient at all. According to numerous US federal government testing reports, this population is performing levels 2 to 2+ on the ILR language proficiency scale out of a maximum of 5, despite their better English skills. This level represents only minimum communicative competence. A linguist, by contrast, should typically achieve level 4 on this scale. However, most rank-and-file linguists also only score 2+, with exceptional scorers reaching level 3.

Corporations can indeed look to language service providers for superior services, but in practice, the typical business models used mean that these providers often fail to deliver. Given the low rates LSPs offer their translators and their policy of “looking the other way” on cheating, even linguists scoring ILR3 or ILR4 are forced to focus on copying and pasting machine translations in order to make a living wage. To get around the cheating issue, some corporations have set up internal translation departments. These corporations, however, have no idea how to manage their own translation departments, and thus wind up staffing linguists with abilities inferior to those of their technical staff.

In Japan, one corporation even decided to mandate its entire staff switch from Japanese to English for everyday operations, so strong was the need for technical staff to do linguists’ jobs. Nonetheless, as seen in Tencent’s failed North American launch and ByteDance’s woes in the USA, the model actually carries a very high risk of causing misunderstandings. Siemens, for its part, relied more on bribery than effective communication and was eventually exposed, with witnesses saying that ”bribery was Siemens’ business model.”

To put it another way, in order to deal with the dysfunctions of non-Western European language pairs, the world developed a quasi-colonialist model for engagement. Various countries would use very low-quality English, making cross-border law largely impossible, while the use of bribery to get things done became normalized. Look, for example, at how much bribery GlaxoSmithKline was alleged to have done to sell medicines in China, or the extent of Walmart’s bribery campaigns in Mexico and other countries. The model was thus developed because policymakers eventually realized there was “something wrong” with this picture, noting that nations receiving very large amounts of bribery often spiraled further into dysfunction and ultimately became klepto-states.

Getting Competence Right

As we’ve seen above, guidelines have long established what’s necessary for a translator to achieve competence in a specialization: strong raw language skills combined with subject matter expertise in a field. The current prevalence of low-quality, misleading statements about Chinese law in society is largely the result of attempting to separate these two competencies—language skill and technical knowledge—into two competing specialties. Organizations hire either a translator with very poor legal knowledge, or rely on a lawyer with very limited English skills produce English translations. Actually, both knowledge domains are essential and must be combined.

The language knowledge domain generally requires proficiency at ILR3 or ILR4 to be effective in translating legal documents. Much of what is taught in so-called legal English classes actually derives from translations of documents originally done from Chinese to English, particularly translations that were rushed or done at low quality to save costs. Additionally, legal English instruction for lawyers frequently involves memorizing word lists out of context. Neither approach provides better than ILR2 or so competence. Instead, very broad reading and study are needed in order to achieve genuine language proficiency.

Secondly, knowledge of the subject matter domain is equally essential, but is often approached irrationally by translators. Logically, someone aspiring to be a translator in a field like business or law should be reading about a lot of business and law to improve their second-language skills. Instead, many tend to focus on entertainment content like television shows and romance novels. This misalignment partially stems from English classes that prioritize “fun” or entertaining materials. However, only about 20% of demand for translation is for entertainment, while approximately 80% is for work productivity-related needs, such as patents, contracts, medical diagnostic reports, and financial statements. The language used in these documents is typically derived from the profession and the real, tangible realities professionals work with. Only by prioritizing professional-related learning materials can translators become effective in their fields. I recommend that all translators spend an extra 400 hours a year outside work, every year following graduation, to master this language and develop the necessary expertise in their chosen fields.