Translating metaphorical or indirect language from Chinese to English is one of the great puzzles of the field. Often, the resulting English translations become incomprehensible, and many translators have simply given up. Many resort to a victim-blaming mentality, believing that “foreigners don’t understand our culture; therefore, they cannot understand a translation of it.” In my observation, however, there are no translation problems too big to solve, only a lack of evidence-based translation mindsets. In this article, I’ll explore a highly challenging translation problem and describe how it can be solved with the application of Skopos Theory and science-based translation methodologies.

A Puzzle

I recently read a research paper that describes a particular long-standing puzzle in Chinese to English translation, that being the translation of the Chinese word wenming into English, as it appears in a variety of government policies. The paper, published in 2023, discusses and adopts the Halliday model of systemic functional linguistic analysis (SFL), but doesn’t get too deep into it. Having spoken with academics out in China, I recall being the only proponent of SFL for translation analysis up until around 2022, when the idea of applying the scientific findings of linguistics department researchers to translation work gained more currency. Thus, I assume that the lack of thorough analysis in this respect is largely due to a lack of familiarity with sociolinguistics and cognitive linguistics.

So, I’ll provide my own take, starting with cognitive linguistics. Like all things, metaphor mapping in Chinese policy discourse is quite essential to the language. Mandarin Chinese is relatively unique in that abstract and academic ideas are often used as metaphors, and the basic idea of metaphor mapping is using familiar concepts to represent and understand more abstract and complex ideas. For example, a “high” tone is something that English has used as a metaphor for sounds for centuries, long before physics even knew the mechanics of vibrational frequencies. The word “civilized” has a similar function to this: in its most basic form, wenming refers to civilizations identified through archaeology and describes the process by which primitive tribes developed arts, culture, and later on writing. In policy contexts, wenming is used to describe a whole lot of things loosely connected with the idea of a civilization developing, and according to the official rules, this can include concepts like a hotel that has a high level of service and listens to its staff. Thus, the extent of the word wenming extends far beyond the English word “civilization” in the policy domain.

Systemic Functional Linguistics Concepts

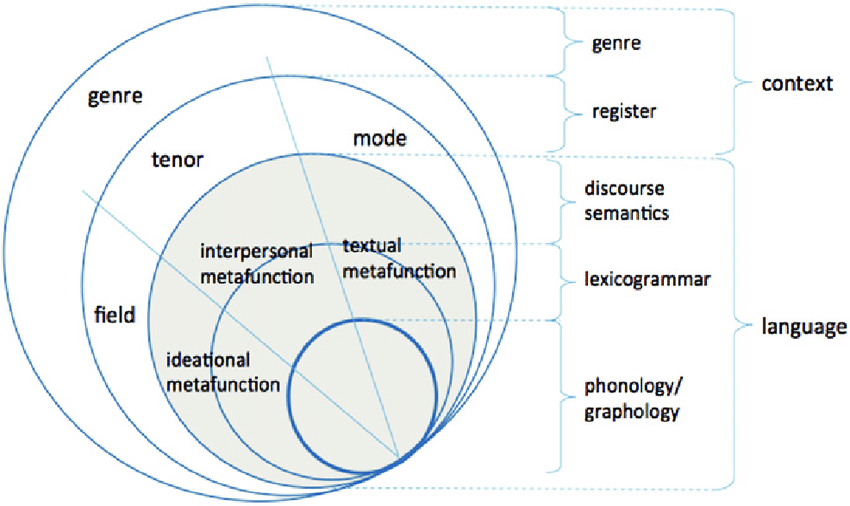

Systemic functional linguistics can be very helpful in assessing the meaning of wenming in its policy contexts. To get us started, let’s take a look at the standard systemic functional linguistics diagram from this paper by Jing Hao:

Starting with the outer layer, the general social practices related to the word, we can see that this is actually a regulatory policy context. That is, the regulator wants to encourage all things “wenming.” For example, in the hotel context, issues identified by regulators would be people cutting in line, the use of gutter oil food, staff yelling at customers, management failing to pay wages for months, and housekeepers ignoring puddles while chain-smoking in a corner. The regulator wants to solve all of these issues, often motivated by tourists leaving reviews about China, and not just specific hotels or restaurants. In this case, the term “civilized” has a vague fit here but usually just leads to confusion once hotels and businesses are involved.

Next, we should consider the discourse itself and how the language is used. Linguists identify three language functions here: the ideational function (expressing ideas–field), the interpersonal function (interacting with others–tenor), and the text structure (textual function–mode). Above, we gave a pretty good idea of the field, the regulation of personal behavior, especially in public. The challenge we’re focusing on is the idea of calling a hotel “wenming” and why regulators want to improve tourists’ overall experience. The basic idea is that businesses should provide high-quality, pleasant experiences. This involves adopting business ethics, professionalism, and etiquette — qualities that people like and not merely put up with. These concepts are actually totally typical in Western societies, with organizations like the Better Business Bureau that refer to all of these as “higher standards” in the specific context of businesses.

Textually, policy papers and thought leadership will emerge at the top of the Chinese regulatory system, with agencies making specific rules and handing out administrative determinations. The “wenming” case is no different: the agency will establish specific rules about who qualifies for an award and then make plaques that can be displayed in hotels. Indeed, these rules are very specific, and ethical business practices like making payroll on time and honest dealings are explicit factors for an agency making such a determination. While the US and UK do have a similar textual structure for business ethics, these are generally overseen by occupational boards, such as those for cosmetology, that advocate similarly for “high standards.” Unlike the centralized, top-down approach used in socialist systems, akin to Plato’s Philosopher King concept, these boards operate through a more centralized, bottom-up procedure reminiscent of medieval guilds.

Finally, the interpersonal factor in the linguistics paradigm is where an analysis of the meaning of a word can encounter severe difficulties. Interactionally, in rapidly urbanizing developing countries, people from rural areas move to urban areas en masse and are dropped into a totally different social structure. In traditional rural communities, everyone knows each other, and interactions are governed heavily by relationships and reputation. David Hume described this dynamic in his Treatise on Human Nature when discussing the reciprocity among olde English farmers in his account of ethics; it’s a part of every society’s history. When these populations are suddenly integrated and moved into a city, however, everyone is suddenly a stranger and relationship and reputation-based interaction stops happening.

Prior to rapid urbanization, Chinese cities were very orderly places, as evidenced by archival film footage from the 1920s showing people lining up in good order. This, however, changed by 1985, with footage showing people pushing and shoving. Nevertheless, the “line” has made a comeback in recent years. In the 1980s, city-going regulators from the old days of patiently lining up suddenly needed to turn the influx of migrants into proper city slickers, to get them to stop doing things like poisoning food. As a handful of regulators, communicating this to 500 million shoving, jostling mass of people was difficult. To simplify a complex topic, they used imagery of the Tang dynasty civilization (wenming) as a mapped metaphor for what the BBB and Western occupational boards might refer to as “high standards,” including not only etiquette but also basic ethical practices like refraining from poisoning your customers or swindling people. The main purpose of using “civilization” as a metaphor in this interactional context is that the audience may react dismissively to suggestions of “high quality” or “high standards.” The notion of “civilization” as a metaphor, however, is particularly effective interactionally because it implicates social status in a “face” based culture where one’s moral and ethical standing in society is essential to one’s sense of self. Thus, we can see why the metaphor would be used.

Skopos Theory is particularly useful when translating mapped metaphors. In a regulatory or news media context, using the underlying concept of the metaphor is more effective, since a person outside the source text society may not have any background in Chinese metaphors. In the context of cultural translation, if teaching about culture itself and this development as this article does, using words like “wenming” and “civilization” in the Romanization can help readers understand the cultural concept itself. Let’s now turn to how to translate what regulators in China are saying.

In the translation context, we have some evidence about interactional discourse in China among native English speakers. During the gutter oil crisis, expatriate doctors in international medical centers would often warn British patients that “standards are lower here,” whereas Chinese regulators would label this as not being “wenming”. At the same time, personal behaviors like cutting in line or spitting everywhere would be described as uncivilized by English-speaking visitors, and not as a sign of lower standards. Interactionally, in some cultures it’s not necessary to use a metaphor to encourage behavioral changes. Thus, to communicate the same thing in the narrow situational context of hotels and restaurants in the United States, virtually everyone uses “high standards.”

Looking at United States history, was the country ever in the exact same situation as the developing countries? Absolutely. In the delightfully captioned case, United States v. Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of Coca-Cola, the government prosecuted a famous soft drink company for selling adulterated products, reflecting public concerns and confusion about the use of chemical additives in food. At the time, food adulteration was widespread, and the case led to the development of the BBB and other occupational boards, which advocated for higher standards in America’s rapidly urbanizing cities.

In a regulatory context, I would recommend following the BBB’s discourse semantics in this case and referring more broadly to “higher standards” when a business organization is involved, whereas in individual cases, terms like “civilized behavior” may be more appropriate. This, I should point out, refers to Chinese to American or British English translations as defined by ISO standards. In these types of translation projects, the audience will be non-diplomatic American or British businesses wanting to understand local policy and regulatory standards. Unlike diplomats, private organizations from these countries lack diplomatic immunity and therefore need highly specific, very clear, and usable texts to work with. Thus, applying the linguistics paradigm within the specific cultural context is essential when translating challenging metaphors like “wenming” into English.