A seemingly impossible translation challenge is to determine the corresponding terminology for municipal district types in modern cities. In practice, most translators simply give up and use a direct translation rather than try to figure out what matches in the second language. A reason for the trouble is attempting to rely on definitions for something where written definitions are extremely vague and seemingly synonymous. Fortunately, a linguistics feature known as indexicality can be used handily to perform an analysis and provide a highly robust, accurate translation that can be used for high-stakes and high-value purposes. In this article, we’ll explore indexicality and how it can be used to identify meanings and find correlations in legal terminology, even when definitions for such terminology are very vague or ambiguous.

Indexicality is essential to good legal translations

In linguistics, the concept of indexicality is the notion that a word acts as a sign that points to, or “indexes” like an index finger does, a particular thing in its context. Good examples of indexical signs are the words “I” and “now,” which refer to the person speaking in this context and the time in the specific context. In legal language, you can find indexicals like applicable law, which is the law that would be used in the event of a dispute. The jurisdiction where the contract is signed usually determines which law is the applicable law. Contrast this with relevant law, which typically only appears occasionally in reference books on the law and includes non-applicable law that may be considered persuasive.

For example, Oklahoma oil law often looks at the relevant laws of Texas even though those do not apply. Words with more defined meanings are also indexical. For instance, referring to “the injury” from a car crash uses a sign that points to harms done (injury) and, in the context, narrows it to a specific injury. High-quality language learning programs are deeply rooted in indexicals-based learning, but the low-quality mass-produced ESL education programs used in many countries are not. Chinglish tends to refer to relevant law as “practice,” i.e. judicial practice.

The manner in which the English language is researched and understood in many countries, particularly throughout East Asia, instead uses a kind of word-to-word matching process that seems to have emerged from isolationist 19th-century Japan. Using China as a reference point, instead of indexing words in English to real objects, the educational system instead indexes the English words in “Chinglish” to Chinese words. Instead of pointing at objective things that exist, the English words point at Chinese words and grammar.

In translation, we call this kind of logic word-to-word matching, where words in one language “index,” or point, to the words in another language. The problem with this words are subjective and to some extent imaginary, and to be useful, someone using a word needs to be able to interact with what the word symbolizes. For example, an English speaker can interact with the “Monkey King” by watching movies about him. A Chinglish phrase like “new energy vehicle” that is based on reference to a Mandarin phrase, requires learning Mandarin Chinese in order to interact with the symbols “新能源汽车,” in which case you’d learn this just refers to alternative fuel vehicles (https://www.energy.gov/alternative-fuel-vehicles). Moreover, it defeats the purpose of translation entirely.

In genuine translation using science-based methodologies, one would have to inspect what the word in context is indexing in the source language, then look at the target language to see what language construction is necessary to index the same thing.

Unfortunately, English programs in many schools around the world still use the word-to-word or translation-based teaching methodology. This approach also has the unintended side effect of giving Chinglish methodology a great deal of social credibility. Professional translators and their bilingual clients will need to push back against the lingering effects of word-to-word translation pedagogy from linguists’ earlier high school years. Additionally, applying genuine science, specifically linguistics, anthropology, and semiotics, is actually extremely hard, while pseudoscience is easy. Launching a rocket to the moon is so hard that most countries attempting it, even recently, expect to fail or have rockets explode mid-flight. Translation is harder than rocket science and more likely to cause explosions.

How to use Indexicality in Translation Practice

For an example of a relatively easy indexicality problem in translation, consider translating the word for a cucumber into a local language. This could be done easily by talking to a speaker of the language and asking their word to name a specific cucumber. A more difficult question may be to translate the word for a ”fruit,” as a cucumber may be called a vegetable by the consumers who eat it, despite being botanically classified as a fruit. The indexicality of the word ”fruit” in the production context refers to the growth phase of the cucumber (fruiting) and the saleable part of the plant (fruits). If you are doing food import/export regulation work and translating US regulations to Chinese or even doing a supermarket app, you would need to look at the specific words used in particular regulatory or retailing concepts to discern what would match the intended meaning in the target language.

A bigger challenge is involved when you start translating abstract concepts that include collections of things; a classic example is how a university is a collection of buildings, faculty, and students, and may act through a legal entity and brand but is otherwise abstract. In the context of Chinese to English translation, a remarkably difficult puzzle emerges when trying to translate the jurisdictional divisions of government administration. Translators traditionally punted and simply called the level below a district a “sub-district,” which works well in general contexts. However, if you are doing work like Know Your Customer (KYC) regulation and looking at documents from these areas, a reviewer may not understand what a “sub-district” really is, and lack of understanding can constitute willful blindness under business regulation—a recipe for a big fine.

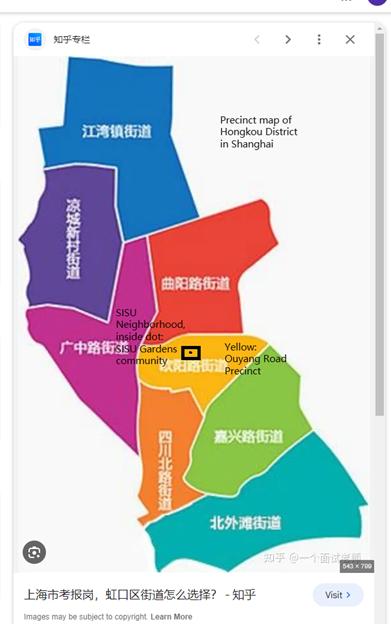

Take a look at this map, for example, which shows the various levels of subdivisions within the Hongkou District of Shanghai. Hongkou District is subdivided into precincts, and within each precinct are several neighborhoods. Finally, there are the gated communities, which we can simply call communities. Overall, there are about four divisional levels used to manage municipal services here. The district administers taxes; the precinct administers policing and public service announcements (PSAs, also known as propaganda); the neighborhoods handle general land use and neighborly relation matters; and the community handles taking out garbage and maintaining the community gate in good order. This lowest level, akin to a homeowner’s association in other countries, is privately owned and managed but nonetheless provides a number of traditional municipal services.

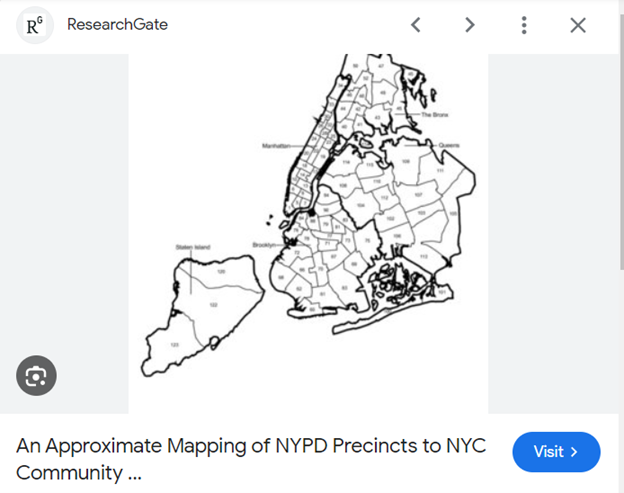

When translating the precinct level (jiedao, 街道), translators taking a traditional approach will typically use “street” because that’s what other translators are doing. They did that originally because, not being familiar with municipal law in China, they thought this word referred to an actual street and not a municipal subdivision level appropriate to the size of a police station. If using an indexicality approach, one would look at the municipal planning maps in China and in New York city; then look at what the subdivision type is referring to (indexing) and what it actually looks like in practice. On the New York map, you can see that the city is divided among several boroughs, about the size of a Shanghai district geographically, with their own executive offices, like Shanghai.

The boroughs are subdivided further into precincts, which is the area a police station would be assigned to administer, much like Shanghai. A big difference is that public service announcements in Shanghai are posted by a special propaganda committee at the precinct level. A possible reason for doing so may be the historic need to post lots of PSAs when eminent domain is being used within a precinct and local police expected blighted residents to put up a fuss. In Shanghai, Kelo-style large scale blight clearance eminent domain was used as recently as 2020 on the Ruihong parcels. The Chinese legislative history recorded in The History of the Chinese Constitution says that economically necessary eminent domain is a major concern for rioting and violence; thus constitutional protections were put in place.

When is Indexical Analysis Needed in Translation?

Indexical analysis is time consuming, so translators should only use it when necessary. For this, I have a good thought process. When translating a word for the first time, or one you know you haven’t thought about, a good question to ask is, “How do I know the word should be translated this way?” Often, the answer is that a teacher in high school gave you a list of words six years ago and said, ”Here, this is the truth!” The high school teacher probably didn’t even speak English herself but rather just memorized a set of standards that guaranteed her a job. Translators then memorize these lists and treat them as truth because ESL students like them could use the lists to take tests, get into college, and then get a job. But corporate documents are not covered by ESL tests, and these same translators are suddenly here translating documents that people like bankers and import/exporters will use to make important decisions. Knowing what the local police precinct has to say goes to 9/11 laws. They have a choice to either de-risk, which means to simply cut off everyone in the region—an economic death sentence—or they may simply ignore the difficulty in understanding and approve of the transaction or underlying business, in which case you could have something like the recent Credit Suisse issues, where an entire company goes bankrupt because it didn’t know what its own people were really doing. Often, it’s essential for someone who is not the translator to point out the issue.

Once you have thought through the translation and realize that you don’t have a good epistemological basis for your conclusion — you believe it to be true because test grades matter more than the truth in school systems, and therefore went with the standardized answer — the appropriate thing to do for a typical translation project is to try to match up the underlying facts of what the word itself is referring to under the indexicality theory with the things in reality to which it indexes. This is basically the above process. In this context, a typical translator will often lack sufficient world knowledge to know what the available words and phrases are for the underlying concepts and can only expediently solve the issue by consulting with a subject matter expert.

Conclusion

Word-for-word translation is a primitive approach where a word in one language “points” directly to a word in another language. Applying modern translation methodologies, we can see that indexicality implies that words should only point to physical things or abstract concepts we have about the world, and the same should apply when doing translation. When it comes to highly abstract concepts that seem to lack even a very specific definition, like municipal law districting, we can use indexicality to “index” common social phenomena and patterns that occur spontaneously in societies to discern how to intelligibly and accurately translate those concepts in a way that will be useful to the end users of the translation.