China is shutting down language and translation programs because the schools aren’t teaching students anything useful. According to a Xinhua state media report looking at canceled translation programs, the underlying problem, “is a lack of integration with technological and economic knowledge” and that programs actually nee to “combine foreign languages with law, finance and journalism.” A report by the China Academy issued a week before this post was published, said recent changes make “language programs some of the hardest-hit. Ministry of Education policies on the subject tell school administrators to focus on student outcomes and to stop selling whatever is popular. downsize by reducing their spending.

To get an idea of the popularity issue, between 2010 and 2020, China launched over two hundred translation programs at various universities, feeding a high demand among students to sign up for these majors. Xinhua noted these programs “emphasized the study of language and literature” instead of something that would lead to job outcomes. In addition to shutdowns, other existing translation programs have been simply ordered to

Post-Graduation Realities

When students in language majors graduate, they often find themselves unemployed, so they sign up for a translation master’s program. But then, they also discover that they are not employable in their industry or really able to do a job that might require a college degree. As a result, the leading occupation for translation program graduates, at least based on word on the street, is to be an administrative assistant, because they don’t know how to do translations. At legal translation education conferences, law firms’ executives often show up and say that the firms do the translations internally because the translation program graduates can’t be trusted to do it.

Skills proficiency for graduates, objectively, is extremely low. A translator needs an ACTFL score of “Superior” to be an effective translator for any kind of professional material, however a typical program graduate has an Intermediate High, i.e. conversational score. China has a very watered-down local translation proficiency test, the CATTI, and according to academic research, 90% of program graduates can’t pass it. The basic reason is, they haven’t learned language and haven’t learned translation. The professors aren’t teaching them.

To get around being noticed producing so many incompetent English graduates, Chinese academics introduced their own language proficiency test, the TEM, as an alternative to the ACTFL and CEFR scores. A big problem with TEM is, it allows the China English academia to grade itself, rather than being held accountable to a standard not under their control.

Schools, however, don’t use TEM. Instead, every translation school has its own admissions test where they independently evaluate students’ English. The very best schools admit students largely based on their English proficiency in the eyes of CATTI graders. Since CATTI is a metric by which translation program quality is assessed, and very few students are skilled in English, they focus on the highest proficiency. However, here as with TEM, the CATTI metric involves academics setting their own standards, and the CATTI tends to focus on topics that students are willing to pay for, such as cultural events. Contrast this to the American Translators Association (ATA) examination, which looks at topics that translation clients need to order.

Students learn popular things like literature

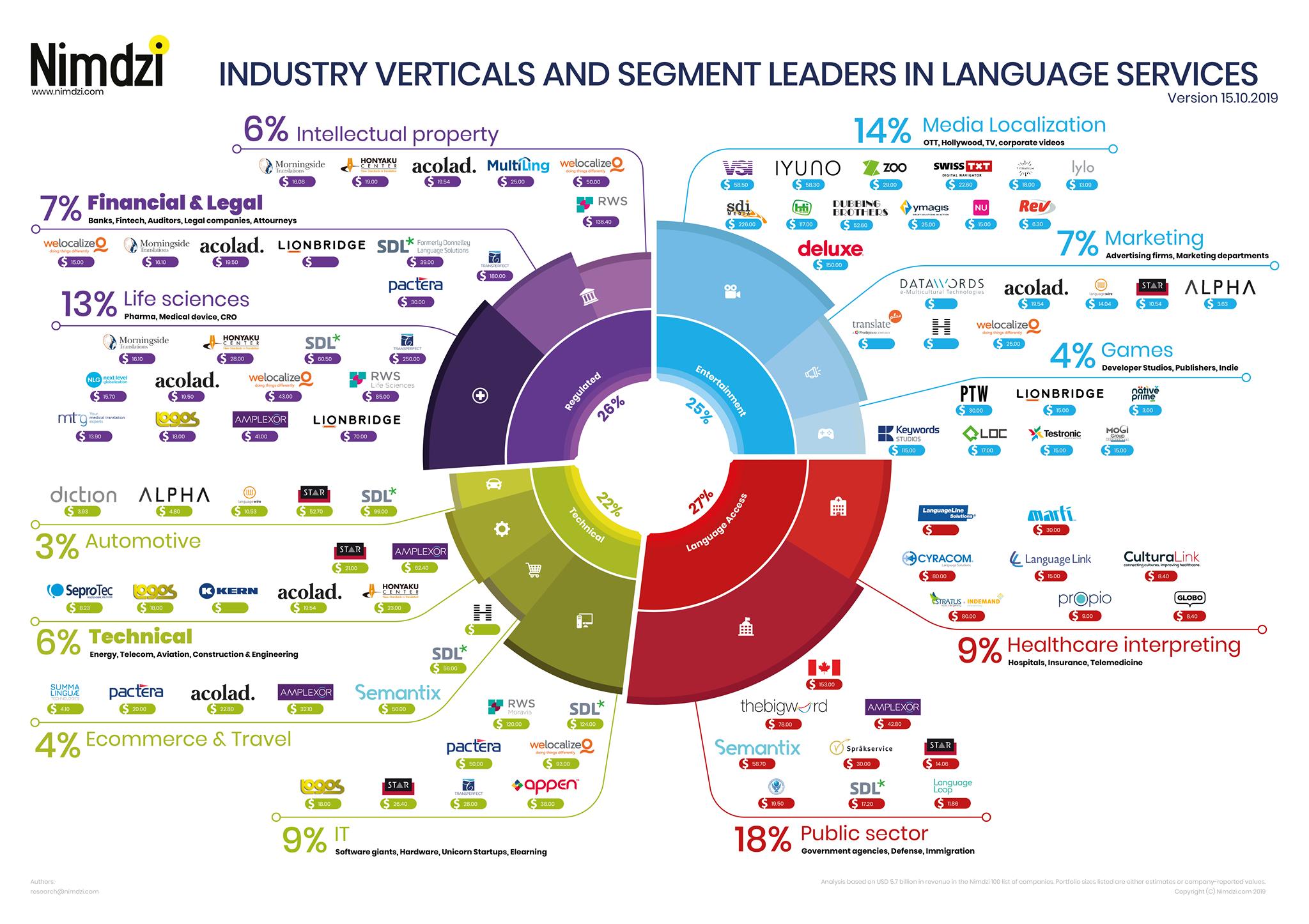

In the China state media, the expert from Fudan University remarks that foreign language and translation students should be directed to law, tech, and finance language and translation tracks. He also notes that few students are studying this. Professor Cai’s reasoning is well supported by industry survey evidence. When Nimdzi studied industry verticals among large LSPs in 2021, it came up with an image that looks like this:

The image shows about half of the picture: high-difficulty fields of IP, legal, and financial are underreported. According to a survey by PaymentPractices.com, about half of the translation work is done directly with freelancers, and not language service providers. Additionally, most legal translation is done in-house by law firms. Thus, among certified translators, you see specialties in finance, legal, and patent that account for the majority of career translators. But even here, we can see that media and games localization is just 18% of the large LSP market, I estimate about 5% overall. But in translation schools, almost all students are focused on these fields.

Misleading Professors

The Chinese government has recently issued a series of policies telling higher education to get its act together. A number of academic papers looking at translation schools specifically found that businesses do not think graduates are generally competent, for the most part, to even intern within the industry. There have also been a number of findings and publications, saying that school administrators are sending misleading employment data to China’s economic administrative agency, the NDRC. In serious cases, administrators have been arrested, and in others more recently, programs simply shut down to force them to stop scamming student tuition money and government grants.

A deeper problem is that students are being lied to by academics within institutions in a fight for that student tuition money. Systemically, Chinese universities are very focused on getting their hands on student revenue and have adopted a higher education model very similar to models used elsewhere. The very young language students overall are very interested in things like literature, art, video games, and diplomacy. They tend to not be interested in things like engineering, law or finance, otherwise they would have majored in one of those fields. The task of universities who want their money, then, is to persuade students that it’s a good investment.

They achieve this in two ways. One way is by publishing success stories about which student went to the United Nations or other prestigious post. Employment statistics on the other hand are kept a secret. Students, not knowing them better, see the handful of success stories as representative, not realizing that there are hundreds of others who were not so lucky. The professors also focus on selling a narrative that studying language translation teaches students “how to think” and enables them to be highly successful in any field. The government economists, however, disagree with the academics, and are trying to find ways to stop them.

Contrary to policy demands that the Chinese universities help drive employment and economic development, internal school decisions are based primarily on overall academic rankings and whether students can be persuaded to sign up for their offerings. This weighs heavily in favor of programs that focus on translated literature criticism, which has a high academic impact, and is a field that closely aligns with what students are interested in. Within schools, administrators measure teaching effectiveness the exact same way Netflix or Apple TV measure a program’s effectiveness: how big of an audience can you get? Contrary to the wishes of the government itself, they do not measure teaching effectiveness by graduates’ future outcome, but rather by how many students sign up for certain classes.

Courses in this specialty are also heavily watered down, often involving no homework and simply professors telling stories about their work or appreciating various works of art in translation. Critical thinking courses in these programs tend not to focus on students’ ability to discern the correct translation but rather explore translation through the lens of literary criticism. Moreover, students really believe what the faculty are telling them about the value of all this, putting their trust in social authority. Without readily available employment statistics about outcomes for students, there is no way for them to discern what’s false.

As a result, institutions are taking bucket loads of tuition money and are willfully blind to employment outcomes. The government is responding by simply ordering programs to be shut down.

It’s a Corruption Issue

The situation in Chinese higher education can be most accurately characterized as a corruption issue, and program closures/downsizing are a regulatory anti-corruption action. That people in China aggressively use the state as a platform to scam innocent victims is nothing new or controversial, China’s President has called corruption one of the country’s biggest problems. Arrests, including the faculty for corruption, have been incredibly widespread. What the government is dealing with in these reports, is basically under-the-radar corruption where state schools are used as a platform for scamming students, not unlike Trump University.

Much of this situation has to do with two factors in China’s system:

- Most higher education institutions are in the state sector (or contracted licensees)

- How China adopted a Western regulatory model with some speedbumps

The problem is, within this kind of regulatory bureaucracy, individuals in the organizations behave differently than in Western bureaucracies. Specifically, there is very little horizontal cooperation between different agencies. This creates a situation where the government does not have a lot of control over what institutions are doing, and those state institutions are thus easily captured by private interests and can be run for the benefit of faculty. If those institutions are not performing well, they are very hard to get rid of and turn into an educational equivalent of the China state sector’s zombie companies.

The way this plays out on the ground is, even if the Chinese universities under the Education Ministry are all technically part of the government, the economists at the NDRC are unable to access graduate employment data or information, and instead have to rely largely on those schools’ self-serving promotional materials. Those institutions can, under their seal, send completely fraudulent data out but the institution will have sovereign immunity for those acts.

If you look at the ocean of various China state economist publications about economic outcomes of higher education, it becomes quite clear that they always considered economic data reported by schools to be inflated and misleading. In other countries like the US/UK, what dishonest educators do is tend to open for-profit universities, which get shut down very quickly. In China, those same people instead go into the state sector with the same kind of predatory motives. Nowhere is this more obvious than in foreign language education, if you’ve read about all the “Chinglish” stories in the media the situation is obvious.

Looking at government action, it looks like it’s impossible to make very informed decisions in the face of the enormous lies academics are telling about their value society. Instead, they seem to be playing a game of whack-a-mole and using bulk program closures instead to change supply of graduates relative to macroeconomic demand.

Conclusion

In this article, we saw that China’s language and translation programs are being shut down or downsized en masse because of academics’ interest in selling “snake oil” to gullible students. Within these programs, students were promised a bright future but instead of learning useful skills, they pulled a bait-and-switch on students. Now, the government facing employment and economic crisis, are choosing to simply shut down the schools and lay off a lot of teaching staff.