Unbeknownst to many, seemingly impossible Chinese-English translation challenges can be solved by applying lexicogrammar. This linguistic approach offers an onion model that allows linguists to peel back each layer of expressed meaning. Chinese-to-English translation is no stranger to terminology that seems impossible to translate correctly, and a good starting point is to look for hyphenated phrases appearing in translations. When a typical translator does not know how to translate a particular word or phrase appearing in Chinese, one solution they often resort to is to translate each individual root and connect them with a hyphen. This very same approach can be observed in the term “foreign-invested enterprise,” where translators attempted to introduce the word “foreign-invested” because they were unable to figure out how basic foreign investment matters are addressed in the English language. Moreover, it’s worth noting that this phenomenon is not unique to China; translators working in other difficult translation languages, like Russian, have also used similar phrases in their translations.

The idea of a foreign investor coming from abroad and investing in a business is so commonplace that it would be absurd to require the invention of new pidgin English to describe it. However, without a fundamental understanding of the lexicogrammar theory, translators are often left with no other choice. In practice, if you are not a native English speaker, figuring out how to describe a company that has received foreign investment, and therefore falls under laws like NAFTA, is not an easy task. The expression itself is a compound noun phrase, not unlike “blackberry,” which is a combination of “black” and “berry,” yet refers to a specific plant, not, say, unusually dark blueberries. Translators therefore attempt to create a new blackberry-type word by adding a hyphen. As a result, new Chinglish phrases dominate English-language information about a fairly everyday subject that does not require the invention of new words.

Fortunately, Chinese-English translation has a very effective tool that can be used to identify the corresponding phrases in English. Known as lexicogrammar, this tool was first developed through a British collaboration at Peking University.

Lexicogrammar as an analytical tool

The concept of lexicogrammar is rooted in the work of linguist and scholar Michael Halliday. In the late 1950s, Halliday developed Systemic Functional Grammar, a language structure theory aimed at explaining why humans use language in the way that they do, and to provide a framework for analyzing language structure. Halliday’s theory laid the foundation for lexicogrammar and has been used by linguists and language scholars ever since. Of particular note for Chinese-English translators, is that Halliday studied at Peking University and grappled closely with the many challenges presented by the very different linguistic structure of Mandarin Chinese.

Lexicogrammar is a combination of two components: lexis and grammar. Lexis refers to the words and phrases used in a language, while grammar refers to the way those words and phrases are used. By combining these two components, lexicogrammar provides a powerful tool for analyzing language structure and is one that has gone through many revisions and expansions since Halliday first introduced it.

At its core, lexicogrammar explores the relationship between words and grammar. The basic idea is that words and grammar work together to form meaningful units that comprise language. Studying the relationship between words and grammar makes it possible to gain valuable insights into how language works and how it can be used, which is especially important for Chinese-English translators because it tells us how language can be translated: by converting one lexicogrammatical set to another, even if the languages totally lack common vocabulary or genuinely equivalent vocabularies! The theory of lexicogrammar also emphasizes the importance of context. It is not enough to simply look at words and grammar in isolation; it is also vital to consider how these elements interact in different contexts.

I emphasize the context part a lot since it’s a core pillar of the Chinese-English translation process. Nonetheless, it’s a factor that many of my translation students bend over backward to violate. The issue is so prevalent that I have resorted to recording their desktop activity to see exactly what it is they are doing. Inevitably, I see that virtually every untrained translation student will instinctively try to skip the entire context when researching English expressions, and literally begin keywording each individual word they are looking for. Only those students who master context will ever gain acceptance and recognition as skilled translators.

Lexicogrammar can also be used to analyze the language used in business settings. Studying the relationship between words and grammar makes it possible to gain valuable insights into how language is used in different contexts. These very same insights can then be useful for understanding how language is used in different settings and identifying language trends and patterns. By studying the relationship between words and grammar, it is possible to uncover patterns that are otherwise difficult to detect. This can be useful for translators closely assessing language, as it enables them to spot language trends and understand how language might evolve over time.

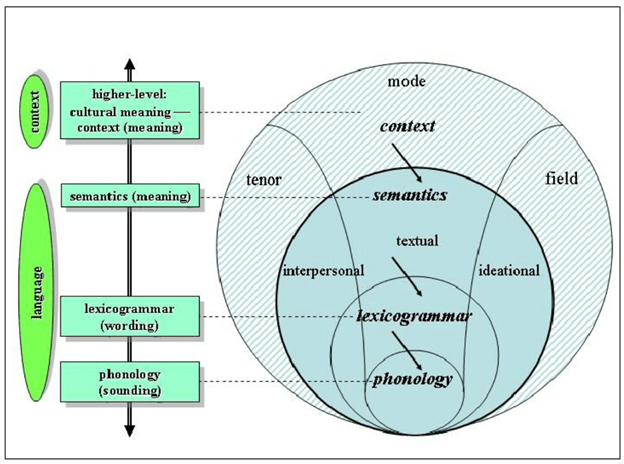

A research paper by Pattama Patpong devised this very clear and useful onion model of how all of the lexicogrammar concepts fit together in linguistics:

Christopher Gledhill is one of the most prominent researchers in the field of lexicogrammar to apply the concepts to translation quality management. His approach to lexicogrammar, which he loosely terms lexicogrammatical analysis, focuses on the relationship between words and grammar, emphasizing how these two components interact to form meaningful language.

In a relatively recent research paper available for free online, Gledhill demonstrates how a lexicogrammatical approach can be used to assess the quality of a translation. This approach is based on certain key assumptions about how language works and how linguistic analysis should be carried out. Gledhill states that the lexicogrammar approach assumes that each sign in a language possesses a specific lexical and grammatical role within the language system, manifested in discourse as a lexicogrammatical pattern. To investigate the customary usage of signs in data, the lexicogrammar approach relies on empirical data, particularly text corpora, concordances, and contextualized samples. This meticulous approach requires the comparison of the text in question against a broader corpus of texts and the use of data triangulation – the comparison and analysis of various types of data sets and samples.

Lawyers here should be zeroing in on Gledhill’s use of the word “forensic,” because lexicogrammar is very similar to the analysis used by courts for centuries in contract, trademark, and defamation disputes. At some point, anyone attending law school studies the Frigaliment Importing Co. v. B.N.S. Int’l Sales Corp case, or the “chicken” case. In this particular case, the plaintiff, Frigaliment Importing Co., alleged that the defendant, B.N.S. Int’l Sales Corp., breached a contract by delivering chicken that was not “fit for human consumption.” The defendant argued that the contract did not define the phrase “fit for human consumption,” and maintained that they delivered chicken of the same quality as the plaintiff had requested. The Frigaliment case is an important decision in contract law because it provides an example of how courts interpret contracts. In this case, the court held that the parties’ intentions should be viewed in their broadest sense and that contracts should be interpreted in a way that takes into account the safety of the parties involved. This decision has since been applied to a number of subsequent contract law cases, and it has helped ensure that contracts are interpreted according to the parties’ intentions.

The Frigaliment dispute originally occurred because one of the parties decided to translate the German word for “chicken” without considering what it meant in English. The court, therefore, had to determine what a reasonable interpretation would be of the contract in English, disregarding its dubious origins, and looked at a huge amount of data on how the word “chicken” is interpreted in various industry contexts. I believe that business translators should be doing the lexicogrammar work to save the parties the cost of going through litigation to clarify what words mean.

Getting better Chinese-English translation results with Lexicogrammar

Lexicogrammar can effectively help solve a lot of these very difficult translation items that produce strange Chinglish expressions such as “foreign-related” (as in the Foreign-related Civil Relationships law) or, as described above, foreign-invested enterprises. By applying lexicogrammar directly, a translator can get started by referring to the lexicogrammar framework outlined above and considering how the language works at a higher level. Specifically, one should start with the context and how it informs meaning. In this case, a “foreign-invested enterprise” is found in international investment law, particularly in regulations like CFIUS and the Foreign Investment and National Security Act.

A translator who reads through these laws will be presented with a difficult puzzle: English has no phrase specifically structured in such a way as to mean a company that has received foreign investment. Yet, as if in a magician’s trick, I was able to refer to such a company using English. Above, one of the insights of lexicogrammar is that the grammar itself forms a part of the meaning together with the lexis (words), and these are inseparable. If you look at every mention of foreign investment in US, UK, or Australian companies, you will see that they all involve the use of grammatical elements to describe and typically position foreign investment. For instance, The Financial Times, Venable LLP (law firm), The Economist, and the World Bank all have multiple documents using syntax along the lines of businesses and companies “that have foreign investors.”

A solution derived from lexicogrammar that has recently been adopted by many law schools and universities in China involves using the word “international” instead of “foreign.” For example, they transform “foreign-related marriage” to “international marriage” using language the rest of the world uses—it was one of my former students, versed in lexicogrammar, who made the finding. Instead of saying “foreign students,” they say “international students,” which indicates that they crossed a border to get here. In the Chinese context, the main reason Chinese regulators use the “foreign-invested” phrasing is that they want to classify, and label, certain companies as involving foreigners. Expressions like “international companies” or “international entities” can achieve this meaning. Different contexts may call for a different translation—the way we talk at the dinner table is a lot different from how people talk in a courtroom. Each translator should look at the linguistic evidence in corpora and come to their own conclusion.

Overall, lexicogrammar offers an essential tool for solving the toughest Chinese-English translation problems, and its approach to analyzing how each language works and how it can be used to express meaning effectively.