Professional reviewers and players of Black Myth: Wukong complained about confusing dialogue and a story that is hard to follow. These feature prominently in the game’s rating rationale, for example how GameSpot gave an 8 out of 10 and complained about dialogue and story. Chinese players also don’t seem to have these kinds of confusion issues, which is actually very normal—it’s actually very rare for any video game to have story and dialogue that confuses its native player base. I also looked at the dialogue and compared the English to Chinese versions, and the Chinese version is much clearer and more logical than the English, thus translation is the culprit. I investigated what may be underlying reasons for translator underperformance, and conclude that Wukong’s development fell into the classic Chinglish + Language Polishing trap.

China’s translation industry is a swamp of incompetence

TAC President Huang Youyi in his book already established that malicious competition in China’s translation industry is leading to crippling incompetence. Below, I’ll give a view from the inside as seen by people familiar with the industry.

In Chinese>English translation, where the market translation rates are just one-third of Spanish and even lower than Japanese, translation companies often resort to extremes to get the job done. On the management end, the persons given authority to manage the translation project are rarely actual experts, rather, they are more often going to be an English major a few years out of school with a CATTI certificate, and they will be made a kind of language Czar and given excessive authority to wreck the project.

The Czar will usually turn the project over to a translation company really good at “malicious competition.” A typical pattern for a highly essential, high profile release is to have college students run the product through Google Translate, then they find “language polishers” who are native English speaking Americans. To get the cheapest Americans, they usually resort to hiring college graduates who are a combination of being drug addicts and wanted criminals. This is an open secret: Vice News previously covered the drug addiction and criminality issues of language polishers in the past, including how they would do the work while on drugs, which powerfully verifies everything we’ve heard through rumors. Fake English teachers in China have also been a long-standing problem, but fake editors sound like a case of self-sabotage Drug addicts do very poor quality work and they don’t really care, so why do businesses keep using them?

Translators in China in these situations secretly love working with drug addicts, because they crave getting constant affirmation and approval from an English native speaker. In schools, we who have taught translation know that even student translators will be enraged if given too heavy translation revision, because they feel “crushed” and shamed about their poor English. Thus, the translation teams themselves will put their egos above the company’s interest. Often, Chinglish translators become convinced of their own genius thanks to the approval of white drug addicts.

I’ve written before about language polishers in Chinese organizations before. They fundamentally exist to make the Chinese language staff look good, not to help the organization succeed.

The above is still hypothetical, so let’s turn to the known facts to see whether they are consistent with the classic Chinglish + Language Polishing localization method.

Did Games Science turn management over to amateurs?

We don’t have much information about the Black Myth: Wukong project other than its credits, news, and rumors from the translation industry. According to insiders familiar with the project, Tencent Games did recommend highly professional translation companies to help localize the product. However, Game Science selected providers based on a test graded by its internal translators, apparently ignoring Tencent’s customer feedback data. The companies it picked don’t look all that competent in English. I visited the website for TransJoing and found they don’t have an English version of their website, for LanGlobal Tech I found their English version was a 404.

Tencent once did the same exact thing themselves, during its much-ridiculed North American WeChat launch, called “lost in translation” by MIT Technology Review The media criticized their awful localization during launch. A similar media story from around that time is how China Airlines translators translated highly racist editorials into the airline’s official magazine.

Did Games Science utilize highly expert translators, or did they use language polishers?

We can find some clues in the game credits.

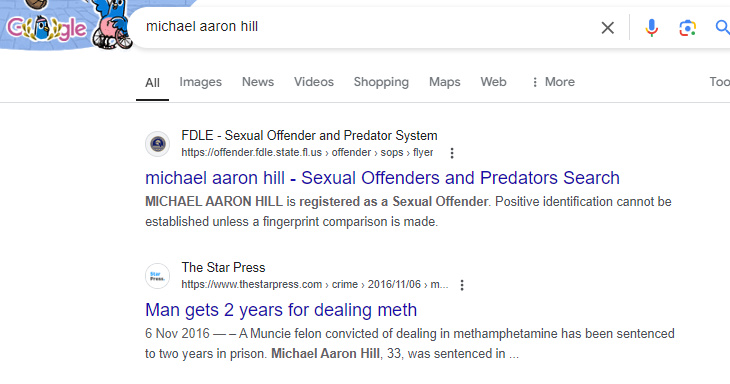

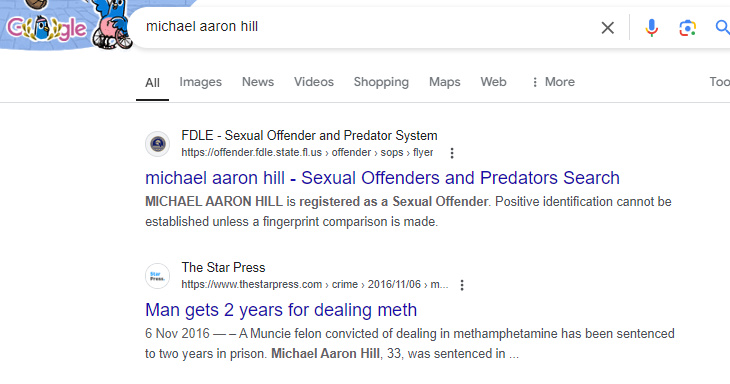

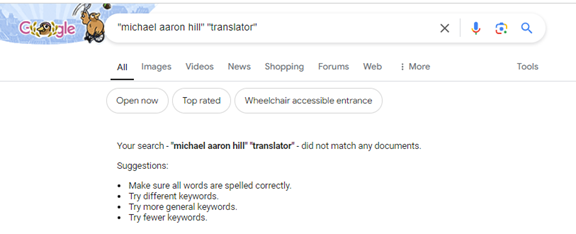

Looking at the credits, I searched in Google for information on their translators and did not find any professional translator credentials for any of them. Even more surprisingly, I put in the full name of a team member—including the middle name—and got criminal record matches on Google to the top of the list for sex offender and drug violations. No linkedin, no professional profiles, no ProZ, just a criminal record. This is what I matched to the list:

But there are no translators by that name, only criminals:

As noted above, hiring drug addicts and criminals as language polishers is very typical, and it’s even typical in America. The American Republican party after all is supporting a convicted criminal and sex offender for President—Donald Trump—it’s not something we could say is a substandard practice in itself. If it weren’t for bad games reviews, I wouldn’t be urging the company to reconsider the language polishing approach. Moreover, I haven’t got solid proof: I did call to ask the company if they had done further background investigations on this person, and got “no comment” and hung up on, but it’s possible that they do have positive identification records showing these are different people. As mentioned above, people with serious drug, sex offender, or criminal backgrounds are often hired to be language polishers because it makes the translators feel competent to get validation from a white person. This is typically the rule and not the exception in China’s dysfunctional, malicious translation industry where translation companies often lie to business managers and make unrealistic promises about quality and speed. Unrealistic processes lead to rank-and-file translators being marginalized and set up to fail.

Translators were set up to fail in the management process.

Based on when localization companies say they had received requests for proposal to work on Black Myth: Wukong, it appears that localization staff unlike Nintendo’s, were not involved with the game early on. Instead, a tight turnaround and SCRUM like “sprint” process seems to have been used to speed things up. This is reflected in the credits where dozens of translators are involved.

I don’t have the game script wordcount, but let’s conservatively assume a long script was used with fewer translators than appearing in the credits. So, 80,000 words split up among 15 translators at three different translation companies is about 5,000 words per translator.

Chopping up five years of development into a two-day translation process is a recipe for disaster. Would you have programmers’ involvement limited to a two-day period? Of course not, the game wouldn’t even function. The result of using a two-day sprint to translate the entire title is, the dialogue will be confusing because there are going to be dozens of lines in the script where it was chopped up. There won’t be good continuity, the vocabulary will often even be different among different translators, and attempts to harmonize it will get poor results.

There is a method to the madness here: American and European games translated into Chinese use SCRUM & Sprint all the time and nonetheless sell fairly well. However, consumers complain about the awful translation quality, but they buy the games because titles like Diablo have very few competitors in the local market. Nintendo and Square pay special attention to translation quality for a reason—translating into global market languages is an upstream battle.

The Chinglish problem seems like it’d be trivially easy to solve for the company, but it keeps happening due to cultural reasons that make it difficult for people to stop.

Neo-colonialist mindset is apparent in Games Science’s translation management

Anomalously, in the credits, we see lots of native Spanish, Italian, French etc. translators rendering into their languages. Having native English translators working on the project could have solved the awkward and confusing dialogue issues. Why didn’t Games Science decide that they should have native-Chinese translators working into those languages if they are happy to have other European language natives involved? The answer is largely in the role of Chinglish in post-colonialism and internalized racism.

Harvard Professor Homi K. Bhabha has studied how and why the colonized people mimic their colonizers. They do not simply replicate colonial culture but instead create a “blurred copy” that subtly undermines the authority of the colonizers. Bhabha emphasizes that this mimicry reveals the inherent instability of colonial rule, as it forces the colonizer to confront the difference within what seems like a replication of their own practices. Through mimicry, the colonized expose the constructed nature of colonial power and identity, destabilizing the hierarchy between colonizer and colonized. Thus, Chinglish is both an opt-in to Anglophone hegemony, but also a means of resisting it. While choosing to participate in Anglo-American hegemony, they also engage in sabotage against it.

The behavior of the translators and the company fit perfectly into Professor Baba’s post-colonialist behavioral patterns. Starting with the translation Czar, consider this is someone who went to major in English for four years at the exclusion of everything else, trying to speak the King’s English and have mastery of the culture just as good as someone in London. Even though America is a much bigger trade partner, they choose the United Kingdom, because England’s military victories and colonization of China deeply entrenched a notion of British cultural supremacy. In China, skill in the King’s English is a sign of being cultured and superior. Nonetheless, the English education programs heavily salt English education in China with translations, often machine translations, leading to a blurred copy of the King’s English—Chinglish—but one that nonetheless demands being recognized as the King’s English, despite its differences.

The post-colonial hierarchy is more easily under stood if looking at ancient Rome. When Rome fell, the Pope of the Roman Catholic church became the supreme moral authority over individual kings, who had physical political power. When the British Empire finally withdrew from Chinese land in 1997, the King of England holds a role much similar to the Pope, lacking physical power but nonetheless being a supreme authority, a King above Kings.

At the organizational level, the measure of an organization’s quality and capacity to provide high quality work is also the King’s English, which reflects a social hegemony in China where the King of England is the supreme authority. For example, Ko Wen-je once said, “the longer the colonization, the more advanced a place is.” This can explain why China’s army uses English in all of its advertisements.

ESL and DIY English translations are the organizational equivalent of skin-whitening cream or Caucasian models for Chinese organizations. It allows them to change their race, ethnicity, and culture from one they are ashamed of, to the prestigious whiteness of their former colonizers. In Brown v. Board of Education, dispositive evidence of white supremacy was that small children if given white dolls and brown dolls and asked which ones are superior, they choose the white dolls. The organizations are simultaneously internalizing the British Empire’s ideology of white supremacy, while also blurring it into a phenomenon we know as Chinglish.

In the Game Science credits, we see lots of French and Spanish people doing translations, but the English translations are done by Chinese native speakers. We can also see “language polishers” present on the staff is to legitimize and verify Ko Wen-je’s theory, that they are advanced people now because they’ve absorbed white British Imperialism, that they are now just as good as their former colonizers. The approach taken by Game Science is different than what Liu Cixin’s and other popular Netflix shows are doing with translation, which is to follow international best practices. The translation project is focused on telling China’s stories effectively, and not on proving how well their team has studied British language and culture.

Otherwise, why is it so important to prove you’re good at English? Why don’t you think foreigners would be willing to learn Chinese very well? Why do you need to get affirmation from Caucasian drug addicts and criminals? The only realistic answer to these questions is that the norms of internalized racism and post-colonialism are driving the project, not localization best practice.

Summary

In this article, we’ve traced the complaints about Black Myth: Wukong from negative review commentary, back to its roots. Throughout the journey, we discovered that they didn’t use specialized, professional translators or localizers. The credits show that a combination of English-limited translators and language polishers whose names appear on criminal registries were used. This is a common psychological pattern of behavior associated with internalized racism and colonialism. To prove that the organization is advanced and sophisticated to their audience, they need to show receipt and adoption of Caucasian and British cultures by their Chinese staff. Hiring drug addicts and criminals to do language polishing gives a strong sense of validation to both internal and external stakeholders within the warped logic of internalized racism stemming from a history of colonialism. Nonetheless, it’s damaging to the product and will cause poor reviews and financial damage.

Continue reading in Part 2 of this series about Wukong, where I’ll talk about how this same Groupthink phenomenon caused the damaging and unnecessary controversy over sexual harassment.