In the context of China’s legal system, judicial precedent refers to an existing set of practices within the judicial system that upper courts and attorneys alike expect judges to follow. An important theoretical distinction from stare decisis and jurisprudence constante is that lower courts are not bound to follow precedents until an appellate court or the Supreme Court formally adopts the precedent as an official rule. This may be done with interpretations, rules, or guiding cases issued by the court.

To understand the approach, it’s important to understand that China’s judiciary works differently from other jurisdictions because under organic law, its judiciary is a subordinate division under the executive, and in line with this approach, has expansive rulemaking authority similar to that exercised by administrative agencies. Thus, nothing is binding on the courts until judges proclaim it is binding.

A key practical difference from other jurisdictions is that the lower courts may spontaneously change how they interpret the law in absence of guidance from a higher court. This was done during the US-China trade war, where lower trial courts spontaneously and suddenly changed the law on layoffs nationwide in order to rapidly take action to prevent a spike in nationwide employment (more detail here).

However, the courts can also establish precedent without announcing binding effect by establishing an expectation or instruction to judges that cases be ruled on in a particular way. An example of this occurred in Siemens, a trademark dispute where the China Supreme Court announced a new precedent for an arcane rule of law with no political significance, and further published a separate article instructing lower judges in the precedent. (article translated here)

Comparative Law

Empirical legal research in the United States has revealed that there are several types of precedent in the legal system under the same name. One type of precedent, executive prosecutorial precedent, from a sociological perspective falls on about the same place as China’s approach to precedent. The main difference In Morrison’s study into the role of the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, he found that the OLC largely follows its own precedent, and more importantly Morrison argues that precedent should have weight for the executive branch, but a different weight than it should have for courts.

In China, which does not have three separate branches of the government and unifies all actions under the executive, the behavior of courts is much like the US OLC’s precedential behavior. For example, when mass layoffs began hitting companies throughout the country, the President apparently ordered that judges interpret employment contract law differently. We know this because, judges nationwide simultaneously changed their court outcomes (see our layoffs article here). Thus, in the practice of judges in China, there is precedent, judges follow precedent, and like federal US Attorneys, may change their precedent at the direction of the President. The main difference is that the US Supreme Court is independent of the President, in China it follows directions from the President in a single chain of command.

Lawyers in China do speak of “judicial practice” when advising clients, while they actually mean precedent, because this is a kind of Soviet Newspeak. In the words of Doroshkov, “Decisions of the Plenum of the Supreme Court, containing explanations on judicial practice, constitute a unique form of judicial lawmaking … born in the USSR.” The USSR Justice Minister Pēteris Stučka emphasized that individual judges do not issue precedent, that the judicial practice is to express the will of the proleteriat.

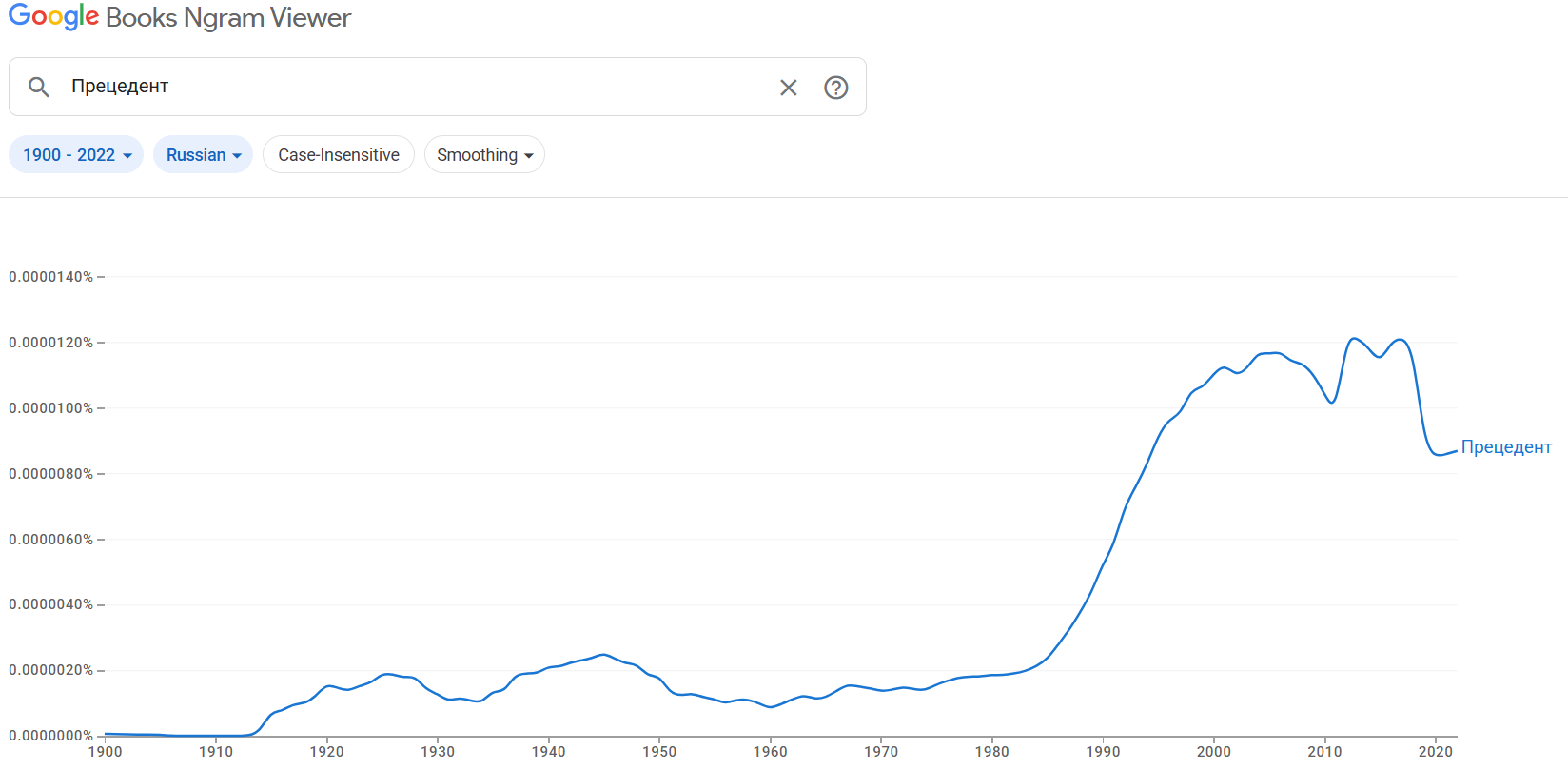

When interpreting what the Soviets meant, it’s important to note that neither Russian nor Chinese does not have a word that means “precedent.” They had a transliteration of the word, pretsedent (прецедент), and the word meant something like “What bourgeoise English judges do that we vaguely understand but is worth investigating.”

Eminent Russian linguist Roman Jakobson looked into a lot of what was going on at the time with Russia and the Soviets as it had to do with language, and at a lot of very specific examples very similar to the precedent<-> pretsedent (прецедент) association, which was adopted into Mandarin through Soviet affiliate institutes. Jakobson said the equivalence of these two things is an “illusion” caused by matching up two code-units that are assumed to have exact equivalent meaning.

Thus, China today has precedent, meaning judges follow their prior decisions unless those are overruled by a supreme authority consistent with Chinese social practice. It does not have pretsedent, which refers to the English judicial way of doing things. When a lawyer says “judicial practice”, they are referring exactly to “judicial precedent” although the semantics are different. But there are differences in these words of which lawyers are ignorant, but are known to scholars polled at the East China University of Political Science and law, known to be the best in their fields.

More specifically, the semantic difference in the early 20th century is not about law in the real world at all. Instead, these are two competing political views about what the reality of societies is at all. Following Blackstone, later English judges like Lord Atkins thought there is a natural, immutable, fundamental law that can be discovered through the common law process (indeed, following Aristotle). Somewhat inspired by Bentham, Marx and Engels asserted law is an expression of nothing more than the will of the ruling classes, and under the Soviets, it is an expression of the will of the proletariat.

However, today very few judges actually agree with what Blackstone says “precedent” is or the law is. Almost all lawyers in American law schools are taught that Holmes said, “law is not a brooding omnipresence in the sky.” That is almost like saying magic doesn’t exist.

Terminology

Chinese lawyers have two words for precedent, one is anli and the other sifa shijian, the main linguistic purpose of this second word is to declare the victory of Marxist ideals over that of Blackstone’s magical thinking. On Chinese television, real world depictions of magic are flatly illegal, and Marxist revolutionary victory constantly celebrated. Culturally, this is very important stuff, but it has no relevance when lawyers are solving real world problems.

As noted above about comparative law with Soviet Russia, From a linguistic perspective, Mandarin Chinese has no single word precisely meaning what “precedent” means as it does in European tradition, although it does have a word for stare decisis precedent. This is most clearly seen in the Chinese expression used to describe lack of political precedent “unprecedented” (前所未有), and other such expressions. Thus, in Chinglish, a commonly seen label is “judicial practice,” a highly direct and confusing translation that came about because of translators’ misunderstanding of the English word “precedent.”

The English word “precedent” literally means “preceding” things, a broad word and not necessarily legal terminology, but in Chinglish, “precedent” (判例), must be legal and must refer to stare decisis. Thus, China legal commentators unskilled in English, may accidentally deny that anything in China is precedented at all.

In highly scholarly legal theory texts, in China, there may be some relevant here, for example that contrast nonpositivist law with the notion of the Chinese democratic dictatorship of the proleteriat manifested through the executive as judicial decisions. Is a judicial practice / precedent distinction helpful to someone not familiar with Chinese or Russian? In this case, distinguishing between various types of precedent as is done elsewhere in the world is much clearer.

In this case, a Marxist Chinese judge should follow prior precedents, but can disregard higher authority where obviously at odds with social well-being. For example, the celebrated Judge Kozinski has remarked in opinions, that California precedent is manifestly at odd in some places with what would be good or minimally logical (Trident Center). A Chinese judge in these cases while following precedents generally, would not follow the text of those precedents where it becomes obvious that they reach manifestly unjust results, especially in the eyes of future higher courts. That is to say, Chinese views of precedent they do not need to wait for an appeal, that they can take into account society’s will. Alexander Bickel has shown judges in the US and elsewhere are generally very well socially aligned, but in the Chinese system there are fewer constraints on lower court judges to choose pro-social outcomes.