Most legal translation projects produce poor results because they use the same approach and often the same exact staff as mainstream translation projects such as marketing. For this brief overview, I refer to the work of two highly authoritative researchers from the well-known Common Sense advisory: Renatto Beninatto and Tucker from The General Theory of the Translation Company. I make three findings about what happens when translation outsourcers serve lawyers within their study: to an outsourcer, (1) Legal translation is unimportant; (2) outsourcing is king; and (3) quality is unimportant. While I have independently verified these three points and to some extent it’s considered “common knowledge” in the translation industry, their opinion as well-known researchers in experts is more authoritative.

Finding 1: Legal translation is marginalized

Beninatto and Tucker insightfully describe the role of the translation outsourcer as follows: “The language services industry includes any and all business related to helping language services buyers to adapt or create content, products, or services to better compete in the global marketplace.” That definition, which revolves around localization and content translation, quite pointedly excludes legal translation. While the authors advocate having localization and marketing translation teams be responsible for “other” fields, the status of legal translation within those departments is relegated to the lowly term “other.” When I worked at a major translation company, project managers routinely considered legal translation orders to be unimportant and uninteresting, something they do not understand nor care to understand, and less exciting than the work of big consumer brands. This is why they tend to outsource these matters–it’s not part of their specialty. Lawyers keep coming back to those companies because they are big, we as lawyers are trained to think that being big is a form of social proof. However, for companies like McDonald’s, H&R Block, or TransPerfect, bigness can also mean you are a high-volume/low quality vendor.

Tucker and Beninatto on page 72 of their insightful book explain how to divide translation projects into quality tiers, each of which gets a different treatment and expects different error rates. For example, product localization must be “very high” and expects a 0% error rate. Marketing content such as press releases is “high” quality, requiring a quality assurance process but they say that a binding contract needs only be medium quality. Legal content ranks just above FAQs and troubleshooting guides (“low” quality, for Google Translate), and in my experience that means it will be rush translated by someone with no certification or training, and not subject to a quality assurance process. A lawyer strives to do perfect work in a memorandum of advice to a client, but when translated to another language, expect it to be riddled with errors.

Why are legal translation projects slotted to the lowest quality tier outside Google Translate projects? From my own perspective from several years of law practice experience, while we as lawyers always expect our own legal work to be perfect, law firms are also routinely grossly negligent in meeting their ethical requirements to supervise the language work upon which the legal service relies. Whereas marketers have experts supervise the translation process and carefully vet the output; most law firms entrust translations of critical legal matters to amateurs. Translation outsourcers misunderstand this lack of commitment to basic legal ethics even as an acknowledgement that sloppy work, documents riddled with errors, and a total disregard for the interests of the client as the core business culture of even America’s most prestigious law firms.

As a lawyer, I would take exception to that statement, but the legal field’s repeated mishandling of translations gives the impression to translation outsourcers that client service is not important to you. If you want to excel where others are failing, this blog can help you provide your clients with the outstanding level of service they deserve.

Finding 2: Outsourcing is king

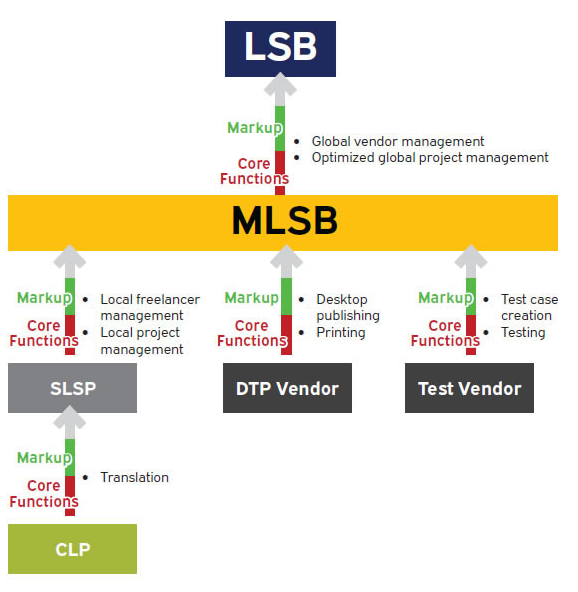

The following figure is described by Tucker as “Each company in the value chain adds value through their core functions and marks up the price to make a margin.” I quote the diagram in whole, though in this blog, I more plainly call LSB “clients” MLSB “outsourcers” SLSP “temp agencies” and CLPs as “contract language staff.”

(Source: The General Theory of the Translation Company. Amazon)

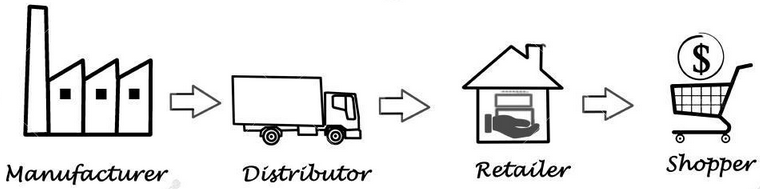

The document is basically a classic industrial supply chain.

Contract language staff manufactures translations using machine translation software; the temp agency distributes translations to outsourcers, who retail the finished translations to clients shopping for translations. A big difference is, you’re buying China manufacturer direct without doing a quality inspection, which always results in buying fake goods.

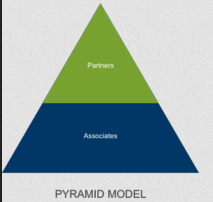

For reference, a law firm’s model looks like any other normal professional service firm:

As someone who has worked as both an attorney and a translator, I can tell you that the way professional legal translation work is organized does not differ from how a law firm works. A partner-level professional works with associate-level professionals, passing on knowledge to associates who are cheaper to employ. In the translation industry model, when you order a contract to be translated, an outsourcer (labeled MLSB) hires a general offshore outsourcer (an SLSP) who then hires a specialist offshore outsourcer (SLSP), and then that company hires a contract language professional, or what we’d call a “temp.” The purpose of all this infrastructure and the reason it’s used is that big companies like McDonald’s and Facebook have huge campaigns where they simultaneously launch in 100 countries with 30 different languages and verifying the quality and placing orders with the quality of the 35 different companies responsible for doing that is enormously expensive. They could need to, for example, have a blog post translated into those 30 languages every two days in a 24-hour time frame; this is why outsourcers exist. Globalization outsourcers also tend to have large in-house teams of localization engineers. Basically, this is a vast machine designed to take English and send out foreign language marketing worldwide in potentially hundreds of languages.

If you are sending a Chinese language contract into that kind of system, then it will also wind its way through numerous outsourcing channels, and you will pay for all of the infrastructure costs while getting none of the benefits. Instead, you will get an abysmally bad translation from an amateur with poor English writing skills, whose real day job is to rewrite English advertisements to Mandarin. The result looks like a long tube, at the same price but with none of the added value.

Finding 3: Quality is unimportant

Beninatto and Tucker also have this to say: “Quality doesn’t matter.” They go on to add, “So if LSPs [outsourcers] do not differentiate based on quality, then what are their differentiators? Usually, they differentiate on their level and types of service they provide to customers.” They also add for manpower firms that “LSPs aren’t working with you because of the quality of your translations.” Marketing guru Neil Patel has provided an explanation that sheds some light on why: international readers were already struggling to understand great content in English, their second language. The local language lacked any content that could compete with what was written in English; brain drain is real and affecting those countries. By translating content to a foreign language, even if full of mistakes, the website gets a measurable boost to its traffic and conversions, and the localization translation earns a fantastic return on investment.

This is what translation companies provide: sales & marketing return on investment. People buy more products than they would without a localized advertisement. A bad translation might provide a better return on investment in a developing country like China or Brazil than a great translation. Thus, while an incorrect legal translation can result in fraudulent misrepresentations, the Avenger’s broken Chinese translation hardly dented sales because audiences are “just here to see the action.”

The way this translation works, in reality, is that many low-cost translators are localizing into their native language, and in marketing localization, you are supposed to change the meaning to suit local preferences.

Beninatto also points out that outsourcers also are all hiring from the same pool of translators, so when clients switch outsourcers, they aren’t switching providers. That is a nice way of saying that you get the very worst translators no matter where you go. He also says clients generally lack sufficient language skills to audit these translations, and thus will often not even notice bad quality. As a result, others in the industry point out most translation companies use a first-come-first-serve model to hand out translation assignments. That means if a novice translator beats a skilled translator to a translation job by just two minutes, then you will be getting novice work, not a skilled translation (even if otherwise advertised). Project managers tell me they can fill projects in 10-15 minutes without much difficulty. You are expected to accept this “flip a coin” approach to quality because you don’t know better.

Actually, this approach is very common for temp agencies in a wide variety of industries, but the effect is amplified in the translation industry, which operates mainly over the internet. Beninatto informs us that outsourcers’ clients generally are people who only think of getting help at the “last minute,” (he compares the translation to toilet paper) and with Chinese translations that basically means the hysterical Chinglish you can find out on the internet. The problem will be exacerbated if you delegate a Chinese-to-English translation to someone whose native language is not English, because then they will not be able to necessarily tell the difference between proper English and incoherent made-up phrases. Moreover, they will likely take bids from multiple broken English translation providers and go with cheap, inaccurate translations, instead of something that can actually produce value for you. When hiring contingent employees in any industry, make sure that the person responsible for hiring is highly qualified within the specialty and can separate the wheat from the chaff. A client doesn’t have their salespeople go out and hire contract attorneys; after all, they have a law firm do it because they have rational modesty about their ability to perform legal work.

Translation outsourcers prefer that their translators are an undifferentiated pool of unskilled and inexpensive labor. Tucker goes on to say that even if Contract Language Professionals try to differentiate themselves by offering a higher level of quality, thus gaining more bargaining power, Language Service Providers can deploy a variety of strategies to take away that advantage to force rates back down. Since translators cannot differentiate themselves to earn higher prices, they surreptitiously find ways to increase their speed, almost always secretly using “good enough” machine translation.

They are, at least in the Chinese market, going extremely fast when they do this, about eight times faster than would be possible for an accurate legal translation. They cannot become experts in translation, so they become experts in cheating. Thus, lawyers should think twice before they send legal documents into a process optimized for marketing translations, as indeed the needs of either are radically different.

An important parallel exists between the above diagram and document review services for law firms. Their “Contract Language Provider” concept mirrors the Contract Attorney used by law firms. Career Contract Attorneys are generally considered to be the worst lawyers, and many firms do not even consider them to be real lawyers. Document review accuracy rates of 70-80% and lower have been reported and accepted by corporate clients seeking cost savings on non-critical work. Likewise, a Contract Language Professional makes error rates of about 30%, and we would generally not consider them to be real translators, because they only have very basic and rudimentary skills. Going to them makes sense for the kind of documents that you would trust Contract Attorneys with to resolve unsupervised: unimportant, non-complex documents that appear in large volumes and impose little risk.

If a document needs to be analyzed by someone at the law partner level, then getting a Contract Language Professional to be the last word on the translation is legal malpractice, because you should know they are not competent to get it right, and lawyers have a duty to their clients to provide adequate supervision of non-lawyer staff. The law firms failing to provide supervision to contract language professionals who make a mess of important documents, are probably the same law firms who routinely send privileged documents to opposing counsel. Quality firms know the best way to supervise almost any expert matter is to delegate such supervision to an expert you know and trust.

Bad solutions: many law firms give up on translators

Numerous law firms with Mandarin speaking staff over the years have simply given up on translation companies due to their outrageously bad translation, and instead simply have their law firm’s attorneys do the translation work, even if they are uncertified or untrained.

In general, the law firm is responsible for supervising the translators. When lawyers translate, it often reduces the level of supervision provided because now nobody is supervising the former supervisor. However, lawyers asked to translate are usually not trained and certified to translate, and thus their translation quality is actually deficient and would not be accepted even by translation companies. While lawyers are great at identifying problems with translations, training and experience is needed to accomplish the task personally. There are two main reasons law firms have attorneys personally do the translation; first and most common, they want to overbill the client. Second, their translation company is providing them awful translations and they can’t seem to find anyone who will do a competent job.