Correct legal translation requires skillfully utilizing the concept of a subset, which lawyers will remember fondly from the LSAT and similar exams as the “Venn diagram.” In my field, Chinese legal translation, a translator who mishandles the subset relationship while doing a translation will produce work that is completely misleading to the average reader because it violates the conventions of legal language. In this article, I will dig a little deeper behind the Logical Reasoning section of the LSAT and bar exams used in legal analysis to explain what this basic concept from Set Theory is and give explanations and examples on how the majority of legal translators are ruining their own translations because they don’t know what it is.

Explanation of subsets

The subset concept occurs primarily in set theory, a fundamental branch of mathematics most people don’t get to cover, but incidentally is extremely important to legal translation and is a skill that is tested by the LSAT. I’ll give a very brief summary of these concepts and how they apply to translation below. Set theory is a branch of mathematics which studies “sets,” or collections of objects considered as a unit. It is a foundational system used to define other branches of mathematics, such as algebra, geometry and calculus. At its most basic, a set is a collection of objects which can be anything from numbers and shapes to concepts. The Set theory deals with the properties of sets and the relationships between them, and allows us to make statements about sets that are true regardless of the objects they contain. Think for a minute about how language in translation works: a lot of phrases, like the “dogs in Central Park” express what sets express. In this case, it would be the set of all the dogs in Central Park, which is a subset of all the dogs in New York.

In addition to the subset concept described below, set theory also includes the concept of equality, which states that two sets are equal if, and only if, they have the same elements. This means that, for example, the set {1,2,3} is equal to the set {3,2,1}, since they contain the same elements, but it is not equal to the set {1,2,4}, since the latter contains a different element. In translation, equivalence occurs when set theoretical equality is present, and Chinese legal translations almost always fail this test due to the subset fallacy.

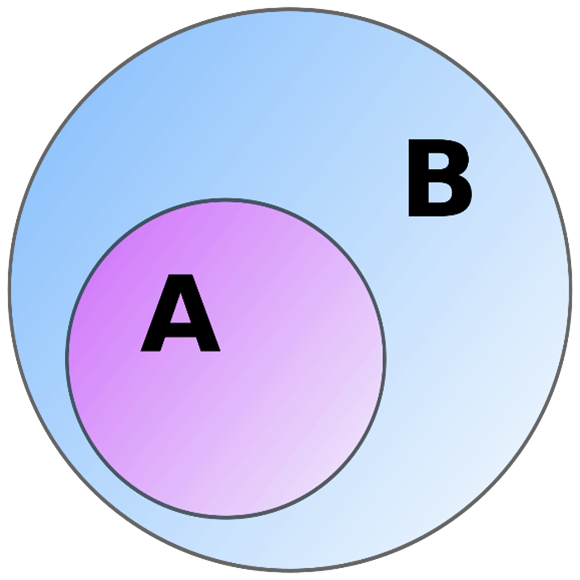

A subset in the set theory is a collection of elements all contained within a larger set. Subsets can be used in a variety of ways, including to solve equations and to understand different concepts. It’s important to note that a subset may contain some of the elements in the larger set, but not all of them, and the elements in a subset must also be distinct from each other. Wikipedia has a very clear diagram in its main article on subsets, which is a good read but probably too technical for legal and linguistics purposes.

Subsets can be used in a variety of ways, and there are many different types of subsets, starting from the pure mathematics ones and moving on to those directly relevant to translation. I’ll give a few examples of subsets that show how clear and intuitive the concept is. In math, which is our starting point, a subset of numbers could be a collection of numbers like “1, 4, 7, 10.” It doesn’t need to be numbers, however: a subset of shapes could be a collection of shapes like “triangle, square, circle.” Finally, a classic example from the linguistic field, which we are exploring today, is a subset of the letters in the alphabet would be a collection of letters like “a, b, c, d.”

If you took a peek at that Wikipedia article, you were probably ambushed by a lot of complicated-looking mathematics notation which I can explain briefly for you. If you have a set of numbers, these can use the set notation (1, 2, 3, 4, 5), and then you would use the “subset of” notation to indicate that the subset (1, 2) is a subset of the larger set.

A few properties define what a subset is in math. A subset cannot contain more elements than the larger set. This means that if you have a set of numbers (1, 2, 3, 4, 5), then the (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) is not a subset as it contains more elements than the larger set. Second, a subset can contain some elements that are not in the larger set. For example, if you have a set of numbers (1, 2, 3, 4, 5), then the subset (1, 6) is still a subset, even though the number 6 is not in the larger set. Finally, a subset must at least contain some elements from the larger set. For example, if you have a set of numbers (1, 2, 3, 4, 5), then the subset (6, 7) is not a subset as it does not contain any elements from the larger set.

You can make your own mental model of a subset to get a better idea of what one is. Start by listing out all of the elements in the larger set; once you have all of the elements listed out, you can start looking for subsets. Look for patterns or similarities between the elements that could indicate a subset. Look for elements that are distinct from each other, as these could also indicate a subset. Once you have identified potential subsets, you can start to refine them by removing elements that don’t fit into the subset.

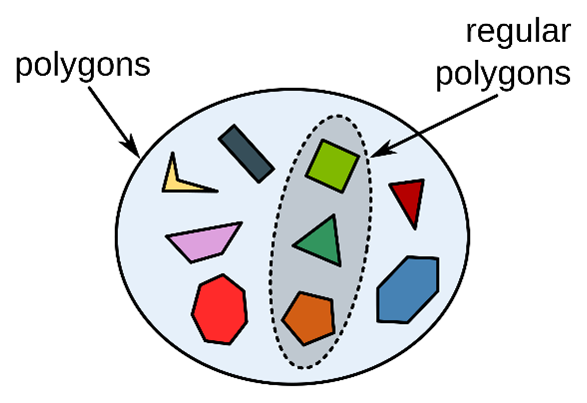

In the linguistics context, imagine that, for example, there is a world with two functional languages: High-context-ese and Low-context-ese. The High-context-ese language has a name for “polygons” and the Low-context-ese language has a word for “polygons generally,” and another word for “regular polygons.” However, in the culture of the Low-context-ese people, referring to “polygons generally” implies that the case is not dealing specifically with “regular polygons.” For example, a Low-context-ese 3D graphics engine where all polygons must be triangles or squares would use the word for “regular polygon.” Legal translators from the High-context-ese culture would generally never talk of “regular polygons” in their translations, yet they intuitively know that these are regular polygons and can describe in detail “polygons that have a regular shape.” The Low-context-ese language, however, requires that this term, this specific subset of a set, be called “regular polygons.” The rules and norms of language usage are violated by not using their customary way of referring to regular polygons, instead using the High-context-ese people’s way, and the Low-context-ese readers have a hard time understanding the translation.

The legal and business environment in Chinese is high context, but not every part of Chinese culture is high context, mind you. For example, family relations are extremely specific compared to English, and there are four different words for “brother” depending on whether this person is your elder male sibling, junior male sibling, or “brothers generally,” which can include both senior and junior brothers, as well as your unrelated male friends who act as your wingman at bars when search of a one-night stand and even its opposite — an unrelated male you go to church with and find terribly annoying but have to respect just because he’s a fellow member. Nor can you simply say “brothers generally” (xiongdi) in Chinese, like was attempted for “polygons generally,” because this will really confuse the person you’re talking in Chinese with since they always expect you to refer to your elder brother using the word for elder brother. Try using “brothers generally” to refer to your elder brother, and people will probably think you’re talking about your wingman or that annoying friend you go to church with. The words “little brother” and “elder brother” are both subsets of the Chinese concept “brothers generally.” However, you have to specify whether the brother is little or elder and cannot refer to the brothers generally because this scenario in Chinese requires very low context expressions.

The same problem when translating from Chinese to English using its high-context language items causes a very large percentage of the incoherent legal translations you see produced from Chinese.

International investment law example

The protection against expropriations in international investment law is a classic example of where translators frequently make this mistake in Chinese>English legal translation. In order to achieve conformity with a variety of bilateral investment treaties, China has a notice requirement for local governments conducting eminent domain where any international investments are permitted. These local government rules are very similar to eminent domain in the United States. If the government wishes to complete a condemnation against a property, it must provide notice of the proposed condemnation in a newspaper such that the property owner may notice it as part of the process. The book and movie The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy parodies this requirement being neglected by space aliens who have scheduled the Earth to be demolished in order to make way for some kind of interstellar highway.

Chinese legal translators frequently translate the “publication” requirement as “announcement” because dictionaries say so, and because it makes sense to them since Chinese law is a high context culture, which is why the wise translators a century ago put that in a bilingual dictionary. This approach can cause a lot of confusion because the notice requirement in an eminent domain proceeding is not really an announcement. If you look at announcements by government agencies, these are usually posted on their news website or made at press conferences. A notice published in a newspaper is technically an announcement, but nobody calls it an announcement because, in practice, the people accomplishing the condemnation often want to try to be as inconspicuous as possible, providing the smallest notice posted on a property or listed in a newspaper in the smallest print possible. Basically, all eminent domain statutes and law books in the United States call the process “publication” and not an “announcement.”

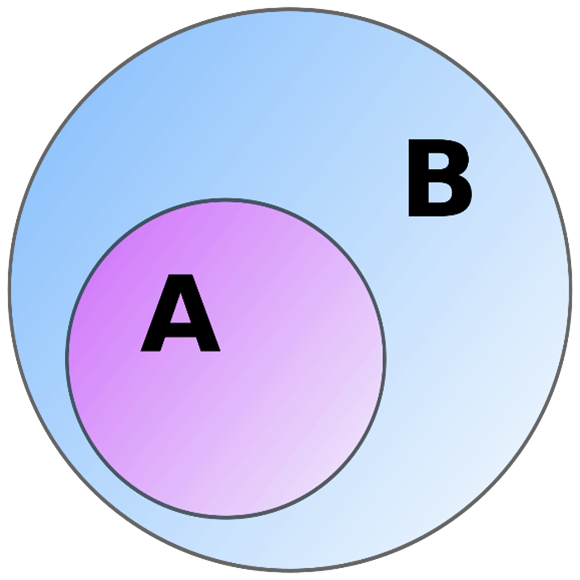

Newspapers do have announcements, and if you look at the announcement sections, they are usually things that people want to be known far and wide, such as announcements about births or weddings in local papers, or some other fortuitous events. The announcements section never contains publication of legal notices for things like eminent domain or seized property. Those go somewhere else. What are the legal translators thinking? Basically, they are using the Venn diagram process to directly translate words based on their definitions, not on how they are used to communicate. Referring again to the basic subset diagram, their native language uses only “B.”

Their native language lacks an “A,” as English does in this case, for publication as a subset of announcements, where usage is mutually exclusive as it is with “elder brother” vs “brothers generally” in Chinese. The translators look for the definition that closely matches “B” and ignore how language is used in practice to refer to things requiring high context. Interestingly, they will never accept their native language used in this way, but when translating into a second language, ignorance of target language norms results in this kind of rigid definition-matching process.

Translators often assume that the reader will attempt to correctly infer the meaning from the translation as if it were a puzzle with a single correct answer. Such an assumption is false, because the readers are not coming to the text knowing that it needs to be solved like a puzzle. Moreover, even if they do try to solve it, the results are likely to be wrong. John Pasden’s blog Sinosplice contains analysis of dozens of examples of him trying to solve Chinglish puzzles, and generally they are not at all solvable. What happens in practice is that the reader will come to the document with their own biases and assumptions, usually something very negative about China, but often will approach it with wishful thinking and treat the document subconsciously like a tabula rasa in a way that supports their existing biases. As an information source, this is totally useless, and the client is usually being led to a translation trap, totally unaware of the danger.