Chinese real estate translation readers are often confused by the strange term “land use rights.” As real estate professionals know, land use law refers to zoning, platting, and environmental law permitting issues, yet the term “land use rights” in China was indeed an invention of translators. Resorting to inventing terms is understandable, even my own Master’s program students default to inventing nonsense terms until they master the basics of Chinese legal translation. Well-trained legal translators know that Chinese law actually closely corresponds to a leasehold estate, though there are cases of common licenses that can be legitimately translated as a right to use. In this article, I will go over the basics of what Chinese leasehold estates encompass, and explain why documents referencing land use rights must be rejected.

Realizing “Land Use Rights” Translations Are Wrong

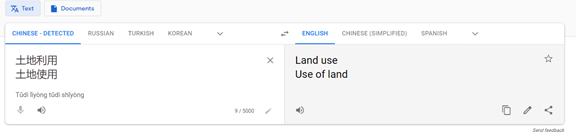

Like English law, Chinese law also includes land use law typically translated as “land use.” This means a reader will not be able to distinguish between land title and land use legal issues within the same translated document. Below, I have input the terms for both land use law and leasehold estate into Google Translate. Despite these being opposite concepts in real estate, Google Translate actually refers to them using the same vocabulary:

The above translation method for Chinese law clearly violates one of the cardinal rules of translation; two opposite concepts that appear within the same context and same document should generally not be translated to have identical meanings. United States law itself has actually already adopted the Chinese property ownership regime in some limited cases, as will be described below. First, however, we need to understand what a Chinese leasehold estate encompasses.

Interest Obtained in a Leasehold Estate

All property during the Chinese Revolutionary period was owned by the state. The initial reform allowed people to own personal property but not land, and made real estate development work very difficult to accomplish. Yantai University Professor Guan Tao explains the legislative compromise that solved this problem in A Comparison Between Leasehold Estate in Mainland China and Superficies in Taiwan:

“China implemented the leasehold estate system in 1988 […]. The civil law leasehold estate refers to the rights granted to a person to use state-owned land for the amount of time provided in the leasehold estate grant contract. Despite the leasehold estate system in Mainland China being an ostensibly broad concept that includes the development, construction, and use of state-owned land, by nature, leasehold estate in China was developed to separate land from buildings. Development, construction, and operation of state-owned land would be impossible if the land and its buildings cannot be separated.” (Translated from Paragraph 3)

Leasehold estates in China are essentially grants to use state-owned land for a given period specified in a leasehold grant contract. The maximum lease period for residential state-owned land is 70 years, and the leasehold entitles the leaseholder to do the same things a fee simple landowner would be able to do. This includes everything from developing, leasing, mortgaging, or reselling the land, provided that doing so does not violate the leasehold estate contract or government regulations.

Leasehold estate holders also have the complete right to exclude other parties. However, these rights are limited to the surface estate as the state retains subsurface rights. Moreover, land zoned for commercial purposes must be in continual use and, if left idle, the state may terminate the leasehold estate. According to research by Li Ying, LLM, East China University of Political Science and Law, the leasehold estate system used in China was modeled on traditional Roman legal norms:

“Leasehold estates are a new concept introduced by the Property Law of the People’s Republic of China. Before the law was passed, the term “state-owned land use rights” was used in law to refer to possessory estate in land. However, legislators considered that there was an improper application of the law since the concept also included collective land rights, which overlapped with usufruct rights. To accommodate traditional land categories, the original term was eventually replaced by “leasehold estate” in the Property Law.” (Translated from Page 9)

Right to Renewal

Since land is leased in China, most people naturally wonder what happens when the 70-year lease term expires. Industrial land is governed the most strictly and can be appropriated if left idle or at the end of its lease term. This should not be too concerning for businesses and, in fact, California, Texas, and New York have many real estate developments that have been built upon ground leases that function almost identically to China’s. The situation is a bit different for residential real estate owners since the possibility that one’s home will be taken away from the family without compensation leads many to feel unsafe. As Attorney Zhang Yingling explains in The Impact of the Civil Code on the Real Property Industry and Recommended Solutions, China has introduced provisions to ensure that residential leasehold estate owners are entitled to remain owners of their homes:

“However, the civil code does not specify important details such as whether the leaseholder is required to pay any renewal fees, how long the lease is to be renewed for, or potential legal ramifications for non-payment (if any).

- The property owner has indefinite ownership of the property but only owns the land upon which the property is built for a limited time. Therefore, homebuyers should pay close attention to the remaining leasehold estate term when looking to purchase a property.

- Residential leasehold estates shall be automatically renewed.

[…] residential leasehold estates are automatically renewed.

[…] 3. Specific rules, such payment methods for renewal fees, deduction and exemption standards, and renewal length have yet to be issued.” (Translated from Paragraph 2)

China’s Congress has recognized the need for a more specific guarantee and wrote reassurance on its website that, “[…] CPC Central Committee requested a resolution on the renewal issue and subsequent amendments to the Urban Real Estate Administration Law or Property Law from the responsible State Council agencies. However, the State Council has yet to officially pass a resolution or amendments. The issue will be further explained once the State Council officially passes resolutions and amends the laws.” (Translated from Paragraph 3)

However, not everyone is happy with legislators’ current progress. In the same official press release, Professor Zhou Guangquan raised criticism that the legislative solution is inadequate for the public’s need:

“The real problem is that leasehold estates in certain places are granted for just 20 or 30 years, most of which have already expired. This is already a tricky issue in provinces like Guangdong and Zhejiang, and one that still lacks a solution.”

Zhou Guangquan further indicated that much of the legislation work has been passed on to the State Council based on the current Civil Code draft:

“This is not a good solution, the issues will remain as they are and there would be no progress in legislation. Lawmakers need to carefully research and issue their opinions on such issues.” (Translated from Paragraph 6)

Current regulation on the renewal of leasehold estates in China varies from city to city due to a lack of national law. This is actually a huge problem that could lead to subsequent invalidation of local government acts due to conflict with national law, as Attorneys Li Lishan and Li Haifu explain:

“In terms of current leasehold estate conditions, the local government agency in the Wenzhou case mentioned above first hired a third party to conduct a real estate appraisal, calculated the total leasehold estate price based on the land unit price, and signed a new leasehold estate contract with the property owner.

Local regulations in Hainan, Zengzhou, and Shangluo provide that residential leasehold estates will be automatically renewed upon their expiration and do not require property owners to request a renewal or approval from local government agencies.

Overall, these practices are in the exploratory phase and it’s difficult to implement an effective system under current law. Any such government practices could be invalidated if they violate the law.” (Translated from Paragraph 12)

Leaseholds in America: Community Land Trusts

One of the most remarkable things about the above discussion is that the supposedly highly unique Chinese land ownership system has a highly similar system in the United States known as a community land trust, which was inspired by ancient Chinese land customs. The effect is remarkably similar to China’s policy of the state stewarding land trusts for the public interest.

The United States community land trust statute divides property into three real property estates: the property owner holds a Leasehold Estate in the land and full title to the house built on the land; a non-profit organization (or a government agency) holds the remainder of the title in fee simple to the land. Typically, the mortgage or sales conditions will have social purpose conditions, for example, a goal of most community land trust non-profit organizations is to restrict occupancy to low-income property owners. Like in China, subsurface oil and gas rights are typically retained by the non-profit, so Texas oilfield royalties may be used to maintain community centers.

The American Community Land Trust System is essentially identical across both systems down to the reservation of mineral rights to the fee simple owner, but the main difference is the kind of entity that administrates the land trusts. In the United States, a non-profit organization is set up to develop the land and be responsible for the administration of the land trust, with a property owners’ association separately responsible for common area management. In China, a government agency is responsible for all aspects of land management, which is state-owned, but construction and common area management are typically outsourced to a construction company, which continues to be responsible for maintenance and property management, typically under the direction of its internal Communist Party organization.

Translation Reasoning

Why should translators, including those who develop those fabulous machine translation engines, stop referring to leasehold estates in China as merely a land-use right? As the above Chinese legal translation makes clear, all the legal references discussing leasehold estates are talking about a type of common land title, and not about the land use rights. Mandarin Chinese does indeed have two different words which mean something like to use, liyong, and a possessory shiyong. These individual words, however, actually mean something radically different from each other when included in context-rich phrases. To a Chinese legal translation client, the most important thing to find in the translation is an accurate understanding of what the document is really talking about. Nobody cares about these tiny semantic differences, and nobody will be affected by them.

Translators translating from Chinese to English have been rendering legal texts on property rights unintelligible to their readers as a matter of custom. The original reasoning for the translation from Chinese seems to have been short-sighted and illogical: after checking law books for half an hour, the original translators concluded that China was the first country to develop anything like leasehold estates. They then consulted their dictionaries and found the first word listed as “land,” the second as “use,” and the third as “rights.” For someone with limited English skill, stringing these three words together might seem like a logical choice.

Conclusion

Instead of misleading their readers with made-up terms, translators translating from Chinese should use English’s pre-existing vocabulary for leasehold estates. The conventional translation method, a word-for-word translation, ignores the language English speakers are accustomed to using in favor of dictionary entries.